All blockquotes are from Making the Second Ghetto by Arnold Hirsch, except where noted.

During the first two evenings of disorder, crowds ranging from 1,500 to 5,000 persons battled police who frustrated their attempts to enter the project. Mobs broke off their engagements with the police and assaulted cars carrying blacks through the area…. Blacks were hauled of streetcars and beaten. Roaming gangs covered an area…of nearly two miles…. An “incomplete” list…included 35 blacks who were known injured by white gangs, and the Defender reported that at least 100 cars driven by blacks were attacked. Eventually more than 1,000 police were dispatched to the area, and more than 700 remained in the vicinity a full two weeks after the riot had “ended.”

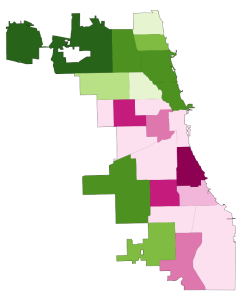

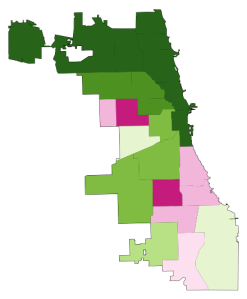

The first time I saw the* ghetto – not just a poor neighborhood, or an entirely non-white one**, but the kind of place where an economic and social bomb had gone off and left its mark on the streets and the buildings and everything else – I was fifteen and taking the train to Michigan. From my seat, out the window, I saw something like this:

I think I was mostly confused. I suspect that’s the case for many Americans, of all kinds of backgrounds, who have grown up in a country that has its problems but which, at some fundamental level, works, upon seeing parts of that country that so clearly do not work. It may be paired with pity, or revulsion, or fear, or anger, but at the bottom is confusion, because nothing we know explains what we’re seeing. How can a neighborhood be so poor, so isolated, so different, in a rich country where people regularly move and mix themselves from city to city and state to state? If the ghetto we’re seeing is populated mostly or entirely by black people, which it generally is, we may think about slavery and other forms of racism, but do we really believe there has been enough of that – even since the 60s? – to account for this? And in the North? To see that kind of poverty in rural Mississippi, near farms worked by sharecroppers, is terrible, but produces very little cognitive dissonance. But in Chicago? In New York***?

This post was originally supposed to be pegged to the Detroit bankruptcy postmortems, but I’ve been busy, and in any case the phenomenon at hand is hardly that specific.

The following weekend, one hundred and fifty white teens armed with metal rods and bottles rampaged through the park, injuring thirty black picnickers. “Hoodlums” broke the windows of more than twenty-five cars…. Officers refused to escort victims into the park to retrieve their belongings, left several black women and children stranded in a park building as the mob attacked, and again rebuked the picnickers for using the “wrong park.”

But that was a particularly stark moment, since it called on all sorts of people to recount a narrative of northern urban decline. And pretty much every single one I read said something like this, from the Boston Globe: “Detroit’s deterioration, which started in earnest after the 1967 race riots were among the most violent in the country’s history, has accelerated in recent years.” Or this, from NPR: “In the 1950s and ’60s, the car companies started moving factories from the urban core to the suburbs. Many white families followed, but discriminatory practices blocked that option for black families. As a result, Detroit got poorer and blacker, while the suburbs got richer and whiter — especially after the city’s 1967 riots over race and income disparities.” Searching for Detroit AND bankruptcy AND riots gets you over two and a half million hits on Google.

This sounds familiar, if you’re a Chicagoan. Chicago Magazine, in fact, published a post in the aftermath of the bankruptcy entitled “How Highways and Riots Shaped Detroit and Chicago,” which declares that the 1968 riots in the latter city “didn’t have the effect of Detroit’s (much deadlier) riots on the whole of the city, but it did permanently damage whole swaths of it while changing the commercial and racial makeup of the city.” It quotes another article: “Marie Bousfield has worked for Chicago’s Planning Department…for 15 years. ‘It’s my view that the riots were the cause of what you call “white flight,”‘ Bousfield told me recently, though she was quick to add that that’s only her personal feeling…. She is certainly not alone in believing that the riots were at least partly responsible. There’s no doubt that there was a dramatic increase in white flight…during the early 70s.”

The 1971 school year opened with the bombing of ten Pontiac[, Michigan] school buses, followed by mass protests…. [White] antibusing activists…vandalized school buses, puncturing radiators with sharpened broomsticks, breaking windows with stones and bricks, and forcing the district to create a high-security parking lot, complete with a bulletproof watchtower. Sweet Land of Liberty, Thomas Sugrue

This is something like a Big Bang theory of urban violence. There were always problems in American cities, the theory says. There were pressures. The seeds of disaster. But the riots of the 1960s, when black people looted and burned entire neighborhoods – their own, but no one at the time could be sure they would stay there – was the catalytic event that actually delivered chaos and unchecked violence. It was the moment when ghettoes like Detroit, or the West Side of Chicago, were born. The things I couldn’t explain from the other side of my train window – those are the “scars” (as the preferred metaphor goes) of the riots.

Monroe Anderson [Tribune reporter] It was almost a riot. When Harold [Washington] showed up and the press entourage showed up, there was this angry– people were approaching the car. People were out of control. I thought that we were in physical danger. And then we get to the church, and somebody spray-painted, on the church, graffiti that said, “Die, nigger, die.”

Ira Glass On a Catholic church?

Monroe Anderson Yes.

This American Life, Harold, describing events at a campaign stop by Chicago’s first black mayor, in 1983.

To get to the point, this is a theory that is tenable only because we have decided to eliminate all other forms of racialized violence from our collective history. When we talk about “the riots,” context is unnecessary: it is understood that we are talking about blacks, in the 1960s (or, maybe, the early 90s in LA), burning and looting the neighborhoods where they lived. As a result, we don’t even have a word for the things that we don’t talk about. We don’t have a word to talk about white mobs burning buildings in Northern cities, or beating or killing innocent people, who wanted to move into their neighborhoods. We don’t really have a word for this:

Estimates of the Englewood crowds varied from several hundred at the riot’s inception to as many as 10,000 at its peak. “Strangers” who entered the area to observe the white protestors and innocent passers-by…were brutally beaten.

Or this:

A crowd of 2,000 descended upon the two-flat bought by Roscoe Johnson at 7153 S. St. Lawrence…. They started throwing gasoline-soaked rags stuck in pop bottles. They also threw flares and torches.

Or this:

In Calumet Park, as dusk fell on the scene that saw whites attacking cars occupied by blacks, white handkerchiefs appeared on the antennas of cars driven by whites so that, in the diminishing visibility, the rioters would suffer no problems in selecting their targets.

Or this:

A mob of 2,000 to 5,000 angry whites assaulted a large apartment building that housed a single black family in one of its twenty units. The burning and looting of the building’s contents lated several nights until order was finally restored by the presence of some 450 National Guardsmen and 200 Cicero and Cook County sheriff’s police.

Or this:

When a black family moved to suburban Columbus in 1956, whites greeted them with a burning cross and cut telephone wires.

Or this:

From May 1944 through July 1946, forty-six…residences were assaulted [in Chicago] (nine were attacked twice and one home was targeted on five separate occasions)…. Beginning in January 1945 there was at least one attack every month…, and twenty-nine of the of the onslaughts were arson-bombings. At least three persons were killed in the incidents.

But they all happened, and they deserve to exist, at least, in our collective memory.

And more than that, the white riots – the 48-hour flash-bang ones, and the slow-burn, once-a-month terrorist bombings – deserve to have as prominent a place in the narrative of northern urban decline as the black riots currently enjoy. Not to make white people wallow in guilt, or even to “blame” them (although those who participated, many of whom are still alive, probably should feel pretty bad about it, if they don’t already), but because any discussion of “what went wrong” that doesn’t mention white violence is just woefully incomplete, and yet that is pretty much the only discussion that we have. It’s like analyzing the causes of World War Two without having heard of the Treaty of Versailles.

And it’s why I, and so many other people, are so confused when they see a ghetto for the first time. Without this context – without the knowledge that the advent of black people to previously all-white urban neighborhoods caused a total breakdown of public safety pretty much immediately as a result of these white mobs – none of it makes sense. So we have to invent a narrative to explain it, and we tell stories about how black people burned down their own homes and businesses, and maybe, depending on our politics, about a “culture of poverty” or “welfare dependence.”

We also, of course, tell a story about economic devastation wrought by de-industrialization, automation, and offshoring jobs. But we never explain why black neighborhoods seem to be overwhelmingly the ones that are decimated, while the white ghetto, as a northern urban phenomenon, is practically unknown. True story: cross-racial comparisons of social indicators like teen pregnancy and street crime that control for neighborhood poverty are impossible in most large American cities, because there are no white neighborhoods as poor as the black ghettoes.

But if whites were so freaked out by the arrival of black people that they bombed their houses and even the buses that their children went to school on, maybe it makes sense that they (consumers and bankers) also pulled every dollar out of the commercial life of their neighborhoods when they decided they had lost the battle against their black neighbors. Maybe it makes sense that these places became as shunned and isolated as they did.

With this context, the black riot-Big Bang theory of urban violence becomes absurd. In the 1950s – years before Watts, or Detroit, or the King riots – Philadelphia lost a quarter of a million whites. Chicago lost 400,000. Detroit lost 350,000. The scale of the abandonment, as with the anti-black violence, was massive from very, very early on.

The web of political and economic and social causes that brought about that abandonment is, of course, extremely complex. I am not suggesting here that white violence was the only, or even overriding, cause. I am suggesting, however, that a conversation about urban decline without it is impossible, both because it was important in its own right and because it illuminates so many of the other causes.

As I said previously, this is emphatically not about white guilt; it’s about getting the story right both for its own sake, and for the sake of getting the remedies right. I’ll take up the remedy side at a later date.

* I vacillated here between using “a” and “the”; obviously, poor, segregated neighborhoods are tremendously diverse in a large and diverse country, and I don’t wish to portray them as homogenous. On the other hand, especially for the purposes of this post, I wanted to talk about the ghetto as an institution, which exists with certain important commonalities in almost every city in the U.S. So “the” it is.

** Of course, originally the word “ghetto” meant exactly that: an entirely segregated neighborhood of an ethnic minority. But in the American context, it has such distinct economic and social connotations that it’s obviously unfit to describe place like Chatham, even if it’s almost entirely black. This, for example, is not what Americans mean by a ghetto:

*** These rhetorical questions are meant to be from the perspective of someone who isn’t familiar with the relevant histories of these places, which I think covers most people. But obviously if you grew up in one of them, you are not shocked to find that there is desperate poverty there.