A few days ago, Pete Saunders wrote a post on “gentrification management”:

I’ve come to the belief that gentrification can be managed. Its benefits can be harnessed; its costs can be mitigated….

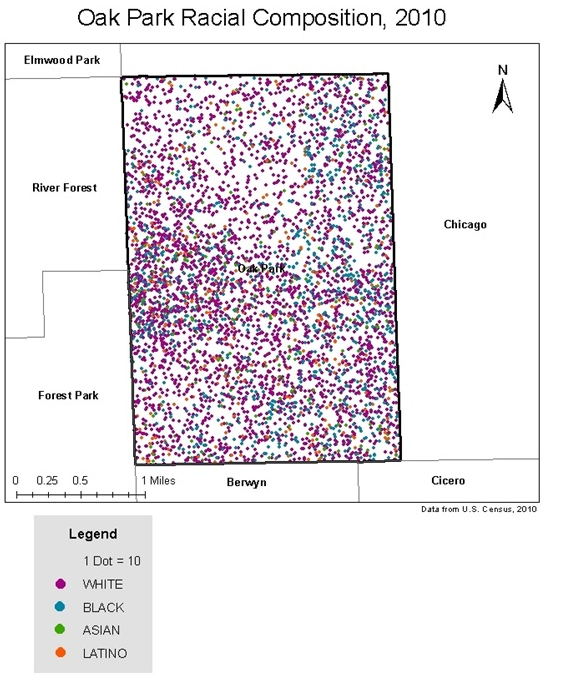

Some six months ago I detailed the efforts of Oak Park, IL, an inner ring suburb adjacent to Chicago’s West Side, as it was faced with racial transition and resegregation during the 1950s and ‘60s. Unlike the vast majority of communities that warily accepted its fate in the face of changing conditions, Oak Park sought to directly confront the issue….

Perhaps Oak Park’s experience can be a template for a gentrification management program.

Perhaps! But, since Pete asks for comments, I will give a few, and they are mostly pessimistic.

My pessimism comes from two things: power, and interests.

The white middle-class and affluent residents of Oak Park had much more power over their situation than the lower- and working-class, generally non-white residents of gentrifying neighborhoods do today. More to the point, Oak Parkers had more power than the people who wanted to move into Oak Park, which is the opposite of the dynamic in gentrifying areas. To start with the obvious, Oak Parkers had more money, which is useful if you’re going to launch a campaign that will require many, many person-hours of work. The fact that Oak Parkers had money also meant they weren’t in danger of being priced out of their neighborhood; the challenge, rather, was to keep their neighborhoods the kind of places they would choose to live, so as to avoid voluntary mass exodus.

Second, Oak Parkers had the kind of social capital that allowed them to do things like set up equity insurance programs to protect homeowners from potentially falling real estate prices during integration. The social power that came with their racial background also allowed them to get away with “encouraging African American dispersion” throughout Oak Park to avoid ghettoization. Imagine the response of middle-class whites being told by some Pilsen neighborhood council that they would be instructed as to which apartments they were allowed to rent so as to avoid too much white clustering: it would not be pretty.

Third, Oak Parkers had the advantage of their own government. Unlike, say, Logan Square, which is governed by a city whose constituents include both longtime Logan Square residents and many of the wealthier potential gentrifiers, Oak Park’s municipal government was responsive only to the interests of a small, relatively homogenous group of educated, liberal whites with, apparently, broad agreement about what the future of their suburb should look like.

Finally, Oak Parkers had the benefit of policy levers that could accomplish what they wanted to accomplish. Without downplaying the real risks they took, and the real novelty of a white neighborhood successfully implementing planned integration in the mid 20th century, by that time American cities had been managing the residential movement of black people, and lower-income people, for many generations. If part of Oak Park’s goal involved making sure the inflow of black families wasn’t too fast, and that it didn’t create new segregated clusters, they had reason to believe that was, if not exactly a slam dunk, definitely achievable. On the flip side, there are no policy levers I’m aware of that can keep relatively wealthier people out of a low-priced neighborhood that don’t also have serious negative consequences for the existing residents of that neighborhood.

What makes this power differential even more important is that the interests of the more powerful party in each situation – that is, existing Oak Park residents and gentrifying newcomers – are very different. Oak Park residents were interested mostly in maintaining their neighborhoods’ “stability”: keeping racial change slow, and keeping property values at their already-high levels. Once an all-out fight against any black in-migration had been ruled out – because they thought it wouldn’t work, or because they thought it would be too costly, or because it offended their political ideals – both their social and financial interests pointed towards slow, controlled integration.

Conversely, gentrifiers have little incentive to promote “stability,” in the sense of minimal change in their new neighborhood’s demographics and real estate values. Even if they have an abstract commitment to “diversity,” gentrifiers are primarily interested in living as close as possible to the middle-class social networks, jobs, and amenities they want access to, while staying within their budgets. (This is obviously not something I can really prove. But A. I have a lot of experience moving in gentrifiers’ circles, and B. the pattern of gentrification in Chicago, clearly moving out from the largest hubs of those social networks, jobs, and amenities, gives a pretty strong indication of what people are trying to get.) That means they will move to the working-class neighborhoods on the edge of more affluent regions of the city.

Importantly, each individual college-educated white twentysomething may prefer that other white twentysomethings stay out of those neighborhoods, but they have every reason to want to move there themselves. If they were kept out, after all, they very likely would be farther from their friends; face longer commutes (or maybe not be able to get to their preferred jobs at all); have worse access to public transit and grocery stores; pay much more for housing and/or transportation; and/or face a much higher risk of crime. This is why Adam Hengels’ point that gentrifiers move where they do because those represent the “best” neighborhoods they can afford is so crucial: it suggests that you can’t get them to stop moving in without seriously diminishing their quality of life. And people rarely, if ever, voluntarily diminish their own quality of life.

And, to close the circle, the residents of gentrifying neighborhoods don’t have the power to force them to do so. Which is why I’m pessimistic that, absent major housing policy reform, gentrification can be successfully managed.