Note: I owe both the concept for this measurement of income segregation and much of the actual data – all of it, except for 2012 – to Sean Reardon and Kendra Bischoff, who wrote a series of wonderful papers on the subject and then were kind enough to send me a spreadsheet of their data from Chicago a while ago. The maps, however, are mine, as is all the data from 2012, and any mistakes in them or in the interpretation of the data is entirely my responsibility.

I think one reason I’ve felt less than compelled by Chicagoland, CNN’s reasonably well-made documentary series, is that its tale-of-two-cities narrative is so worn, so often repeated, that it’s become a little dull. Not the actual fact of inequality – which only seems to cut deeper over time – but its retelling.

In fact, I think the point has long passed at which simply repeating the story of Chicago’s stratification is equivalent to fighting it. For a lot of people, in my experience, it’s the opposite: an opportunity for distancing, for washing of hands. It’s a ritual in which we tell each other that this is the way it’s always been – The Gold Coast and the Slum was written about already well-entrenched institutions, after all, over three-quarters of a century ago – that these facts somehow seep out of the ground here, as much a part of the city as the lake, and that as a result there’s really nothing we can do about it.

But this obscures much more than it clarifies. Inequality has always been a part of Chicago – as it has always been a part of the United States, and a part of humanity – but the forms it has taken, and the severity of those many forms, have changed in truly dramatic ways. Take, for example, today’s monolithic segregation of African Americans: at the turn of the last century, black Chicagoans were less segregated than Italians, and not because Italians were then hyper-segregated.

Moreover, decisions made by people in the city have played, and continue to play, a huge role in determining what those changes look like. Had Elizabeth Wood received any serious support from white residents or their elected representatives – instead of meeting Klan-like violent resistance – the history of racial integration, economic integration, and public housing in this city would be very, very different. This isn’t to say that national and global factors aren’t important, since they obviously are. But neither do we lack responsibility.

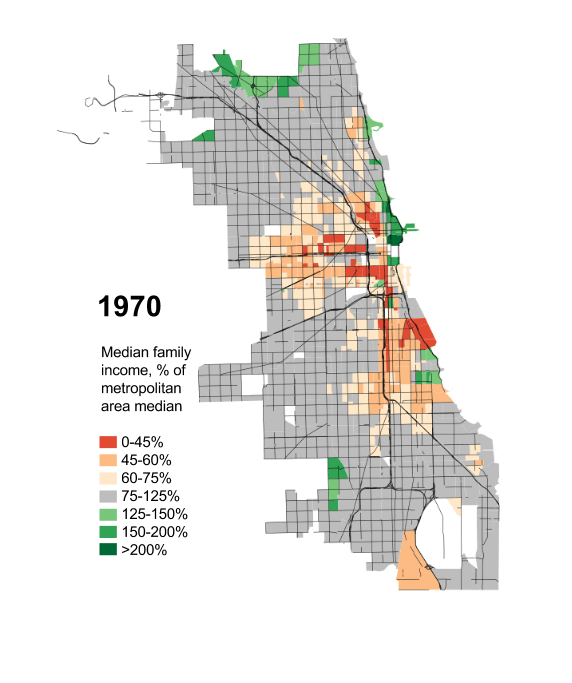

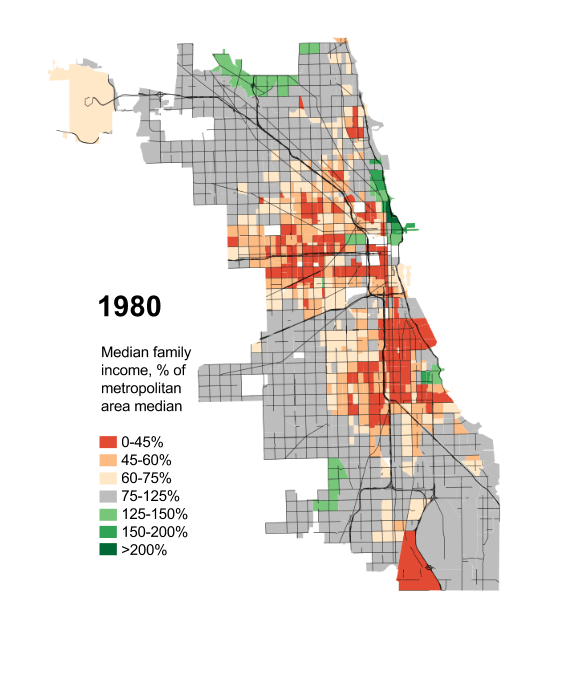

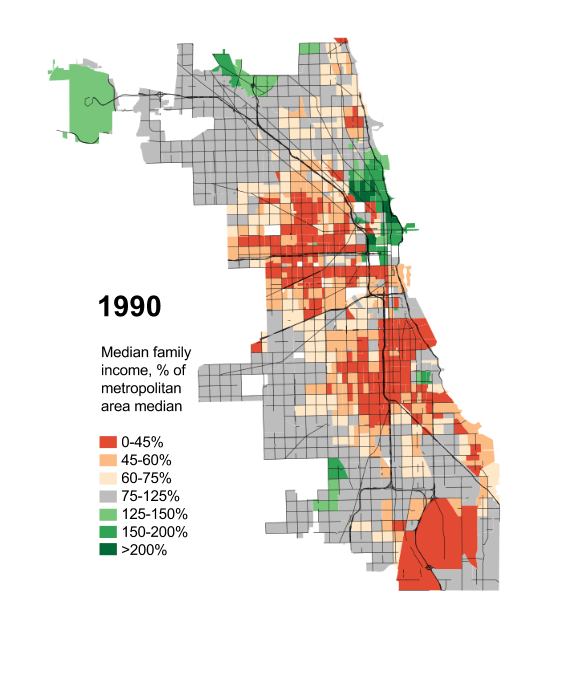

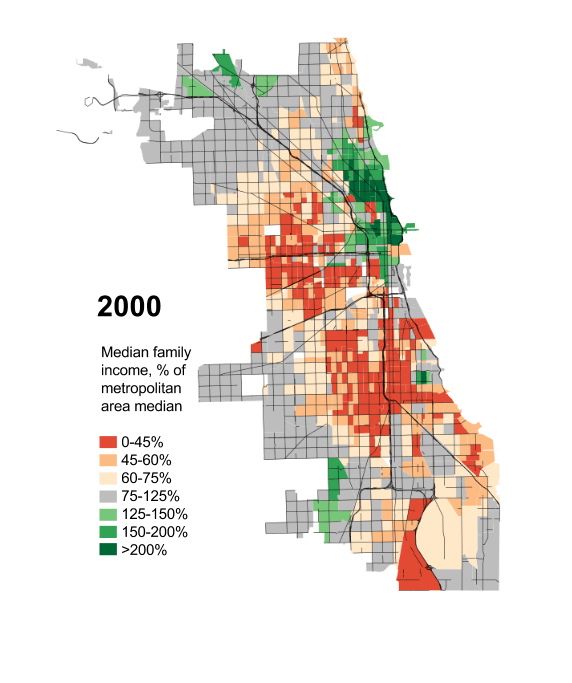

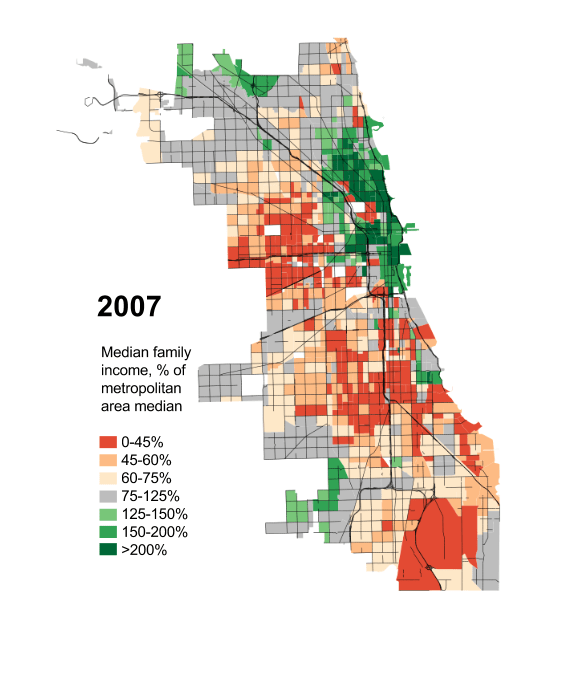

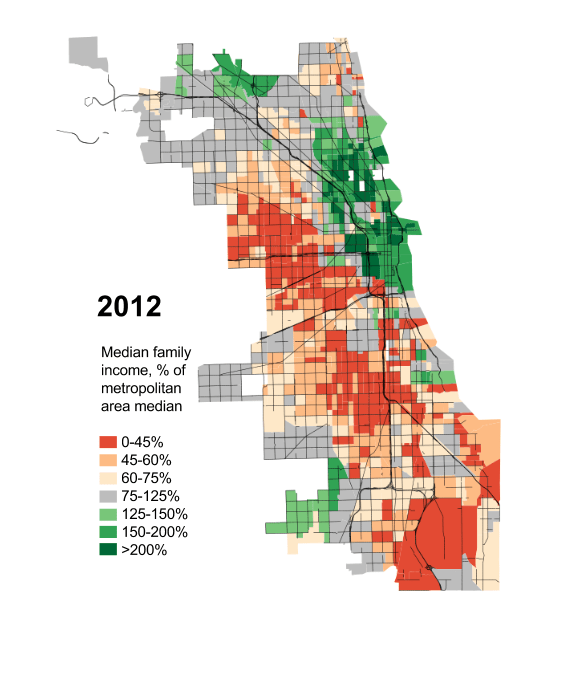

Anyway, this is all by way of introducing the following maps: their goal is not merely to depress you (you’re welcome!), but to suggest just how dramatically the reality of Chicago’s “two cities” has changed over the last few generations, how non-eternal its present state is, and that a happier alternate reality isn’t just possible, but actually existed relatively recently.

I feel relatively comfortable telling the story of how Chicago came to be so segregated by race; I’m much humbler about my ability to explain this, except inasmuch as the ever-widening ghetto of the affluent could not exist without, yes, radically exclusionary housing laws, and I will take that up separately in another post. In the meanwhile, I’ll take a page from Ta-Nehisi Coates and ask you all, if you have some background in this, to talk to me like I’m stupid: what does the literature say about growing economic segregation? Who and what should I be reading?

One last piece: the obvious and immediate reaction to these maps is to see them as a direct consequence of rising income inequality. There is some truth to that, but the researchers from which much of this data came have already discovered that income segregation has actually risen faster than inequality. So that’s not the end of the story.

Anyway, here you go: the disappearance of Chicago’s middle-class and mixed-income neighborhoods since 1970, measured by each Census tract’s median family income as a percentage of the median family income for the Chicago metropolitan region as a whole.