Friend of the blog Ted Whalen asked me this on Twitter after my last post:

@DanielKayHertz large swaths of lincoln park and gold coast appear redlined on the map atop your latest post. what % of the city wasn’t?

— ted whalen (@tewhalen) May 27, 2014

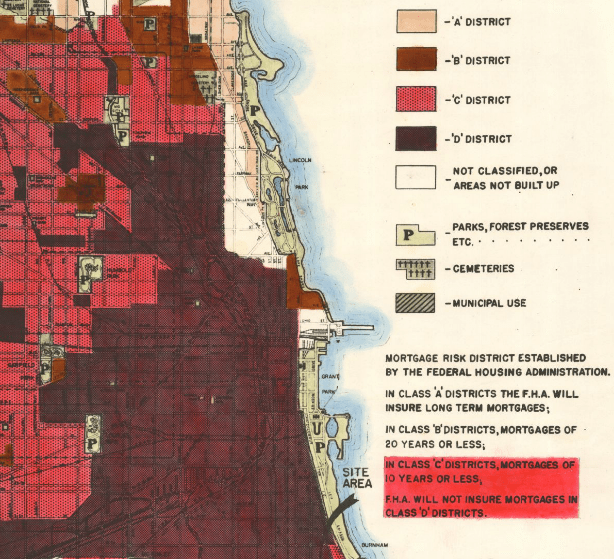

Good point. If you look at the redlining map I posted, you’ll see that virtually all of the city (at least, what I clipped – you can see the full map here) is under some kind of mortgage insurance restriction, and a good deal of it is “redlined” – meaning the federal government refused to insure any mortgages of any kind. Even neighborhoods that today are quite well-off, including large parts of Old Town, Lincoln Park, and Wicker Park, were totally shunned.

For those of you who are unfamiliar with this history, you should go read Ta-Nehisi Coates’ essay. But the short version is that one of the most powerful and far-reaching New Deal-era policies, in terms of creating wealth among the working and middle classes, was reforming the way people bought houses. Prior to the New Deal, buying a house generally involved paying a huge lump sum up front, and/or taking on possibly multiple complicated, short-term, high-interest, generally unpleasant or financially dangerous loans. As a result, not very many people bought houses.

President Roosevelt changed that by creating federally-insured home mortgages that guaranteed certain buyer-friendly terms, including much smaller down payments and, crucially, 30-year payment periods. All of that dramatically lowered per-month payments, which were now affordable to the average member of the broad middle class. In essence, it was a massive subsidy program so that regular people could buy homes. Since homes, generally speaking, grow in value, and because they tend to be the single most valuable asset that most people have, it was also one of the single greatest generators of wealth in American history.

The problem for black people (and cities, and in a moral sense America itself) was that those subsidies were only available in certain areas. Basically, the federal government drew maps like the one above for the entire country, identifying neighborhoods that were too “risky” to insure loans in. One major indicator of “risk” was an aging building stock and “old-fashioned” urban design, which basically meant everything that today’s urbanists hold dear: mixed-use buildings, apartments instead of single family homes, etc.

But another major indicator was black people. Not some proxy for black people, or a sneaky back-door measure designed to exclude them: the federal government explicitly refused to insure any neighborhood that contained black people, or even neighborhoods adjacent to other neighborhoods that contained black people, for fear that soon some of the nearby black people might contaminate it. This was not a joke: in Origins of the Urban Crisis, Thomas Sugrue tells the story of a developer who wanted to build a white subdivision on the edge of Detroit in the 1940s. The problem was that the land he owned abutted a pre-existing black enclave, and the Federal Housing Administration was nervous about insuring loans in the area. To allay those fears, the FHA – the federal government – insisted that the new white development be separated from the black enclave by a six-foot-high concrete wall.

These policies didn’t begin to change until 1968, and private use of redlining wasn’t aggressively battled by federal law until the 1977 Community Reinvestment Act.

Anyway, the result of all this was that a) black people were excluded from the single largest wealth accumulation program in the history of the world to that point, and b) black neighborhoods – as well as many other inner-city areas – were systematically starved of capital that might otherwise have been used to keep buildings in a state of good repair. This was a major cause of their decline.

It’s notable, though, that lots of non-black neighborhoods were also redlined, as you can see in the map above. So if redlining was so important, why aren’t western Lincoln Park and Wicker Park facing the same kinds of problems as black neighborhoods?

I think there are a few answers to this question. The first is simply that up until relatively recently, they were. Wicker Park, before it was the commercial heart of the Northwest Side, was a downtrodden and largely Latino neighborhood with a crime problem. Before that, wealthy Lincoln Parkers near the lake were sure that redevelopment and gentrification would never make it west of Halsted – to the areas that had been redlined.

The second is that those areas became revitalized as a result of an influx of mostly white people whose families had mostly chosen to bring them up elsewhere, largely in outlying urban or suburban neighborhoods where they had been eligible to buy federally insured homes and become solidly middle class or upper middle class, with home-based wealth as an anchor for that economic status.

The third is that while some white people were subject to redlining, the majority weren’t, which created the huge supply of relatively well-off white people who could bring resources back to places like Wicker Park. On the other hand, anywhere a black person successfully bought a home was, by definition, redlined, so a much, much tinier group of them made it to the comfortable middle class. (Even where black income matches white income, black wealth – which plays a huge role in absorbing shocks that might otherwise send a middle-class person back into economic instability, or financing investments in future earnings like college tuition – is usually tiny compared to their white income peers.)

The fourth and final reason is that because of a variety of economic and social factors, white people have been extremely hesitant to move to black neighborhoods. (Read: Federal policy made black neighborhoods, on average, more run-down and unattractive to the average home buyer, and white people also are racist about living around black people.) Combined with Reason Number Three – the tiny supply of wealthy black households – that means that even after redlining was abolished, there was no large middle-class cohort ready to swoop in and bring money back into black neighborhoods. Rather, the legacy of disinvestment was left to fester, and the opening of the broader housing market meant that middle-class blacks could leave for greener pastures. Which was, of course, great for them, but it also meant that even more capital was leaving those already capital-starved neighborhoods.

This may or may not be exactly what Ted was getting at – maybe I just should have tweeted a link to the full map – but it’s important stuff anyway. Read on.