Very often when I say the word “bus” out loud, someone will volunteer that they hate buses. The conversation might go like this:

ME: Bus ridership is down. It’s not clear why.

FRIEND: Have you considered the possibility that buses just suck?

I find these conversations frustrating, because the people I’m talking to are wrong, but I can’t actually get into why that is in a casual setting without being pedantic and annoying.

Fortunately, I have this blog, where the cost of being pedantic and annoying is much lower. So here we go: buses don’t suck. They suck because we make them suck.

Let’s take, for example, the boarding situation on the Fullerton bus at the Red/Brown/Purple L station heading west. This is a stop I board at a lot, because it’s the main way to get to Logan Square from the north lakefront neighborhoods. I am not the only person with this idea, though, so there are frequently ten to twenty, or more, people waiting by the time a bus arrives. Each of these people must tap their Ventra card (or, God forbid, pay with cash) before the bus can move on. If each person takes, on average, two seconds, that’s easily 30-45 seconds spent waiting for people to board. If someone has a problem with their Ventra card, or is fumbling for cash, it can take an extra 15-30 seconds.

That doesn’t sound like a lot, but it’s pretty excruciating to wait through. If you drive, imagine sitting in traffic – not at a red light, but just waiting for no good reason – for 45 seconds. Set a timer, imagine yourself staring at a bumper, and just let the time wash over you.

Moreover, it can cause the bus to miss a green light, which can easily add another 20-30 seconds after everyone has actually tapped their cards.

Multiply this by every busy stop a bus makes – in Chicago, especially any time around rush hour, this is a lot of them – and you go a long way to explaining why buses are so slow. Or why, in the words of my friends, they suck.

But this is not a problem we have to live with. It is simply a result of having decided that everyone has to pay for the bus when it arrives, at one card reader at the front door. Although most people don’t realize it, this is not the only choice. But it’s important: imagine how much more trains would suck – trains, those things that everyone loves – if everybody riding them had to tap their card at one reader when they arrived at your station. It would take forever.

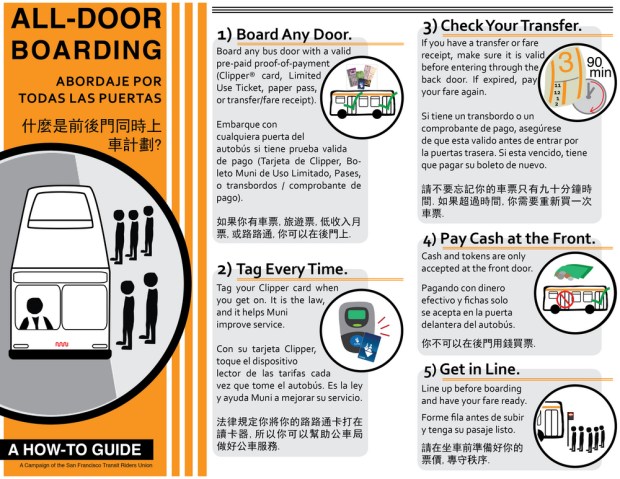

Anyway, one other choice would be to have two card readers: one by the front door, and one by the back. This is called “all-door boarding,” and San Francisco, among other places, does it. As you have no doubt already calculated, this reduces the time required to have everyone get on the bus. Over the course of a ride over a few miles when 50 people or so board, that can make a difference.

Another, even more exciting choice would be to have people pay before the bus arrives. That way, there’s no tapping at all! Just get on and go.

Chicago will actually begin using that system at exactly one bus stop in the entire city once the Central Loop BRT project is complete: one of the rail-style bus stations will have rail-style turnstiles that you’ll have to tap your card on to get through. That way, when the bus arrives, you just get on, like with trains now. Ashland BRT, if and when it happens, will probably also use that system. That’s one reason they’ll be so much faster than other buses.

But you can actually get the same benefit without all the cost of building a station and adding turnstiles. You can do what the MTA does in New York with a few of their bus lines: you can put little kiosks at major stations where people can tap and get a little paper receipt saying that they paid. Then, when the bus comes, they just walk on. No waiting for tapping at all! The downside is that you then need a small security detail to spot-check people’s receipts to make sure they’ve paid, but that turns out to actually not be a very big deal.

Either of those – all-door boarding, or pre-payment before the bus arrives – can make buses suck much less. But this post was really inspired by Sandy Johnston’s response to WBEZ’s story on bus bunching:

What was really disappointing about the Curious City piece is that everyone interviewed–from bus riders to academics to CTA drivers and officials–seemed to take the the fatalistic attitude that bus bunching is completely inevitable and very little can be done to prevent it…. But…[t]here is, in fact, one policy lever that can help the CTA (and other agencies) avoid bus bunching, but it is politically unpalatable to most actors, especially the city’s auto-oriented elite: dedicating lanes to public transit.

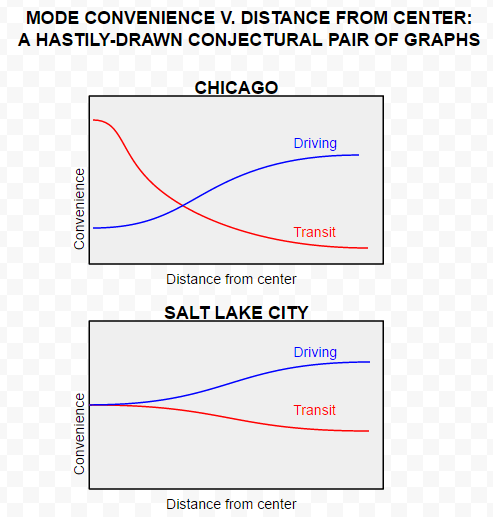

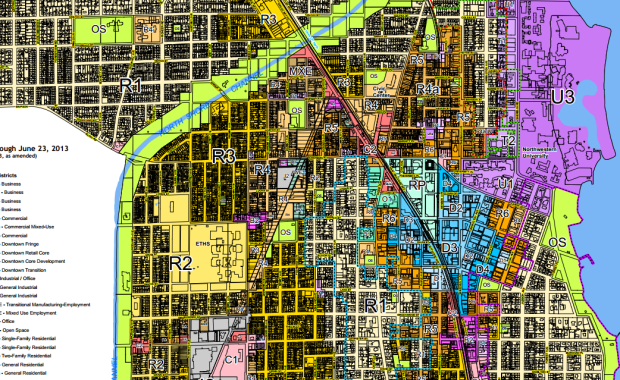

Yes: another way to make buses suck much less is to make the most basic gesture at believing that people who ride buses should be able to get places in less than twice as much time as it takes to drive there, and give them their own lane. When buses and cars share lanes, not only do buses get stuck in traffic not of their own making – sixty people or more regularly squeeze onto a single bus just fine, but that many people in cars could back up a road for blocks – but they have to negotiate pulling out of and into traffic every time there’s a stop, which in Chicago is frequently every block. That also wastes a lot of time.

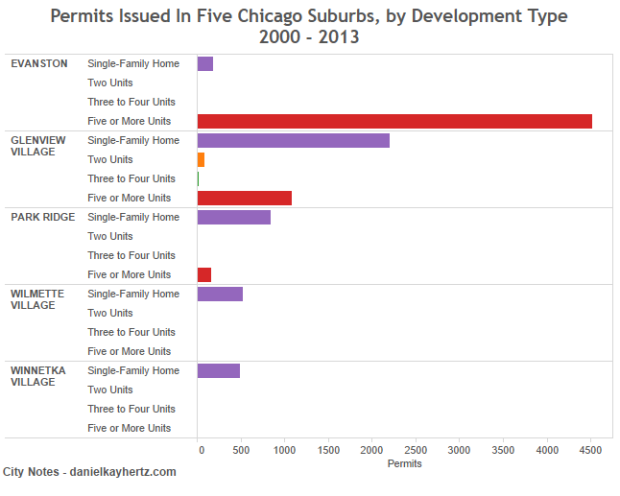

Sometimes people object to bus lanes on grounds of fairness. On Ashland, say, people on buses make up about 20% of all travelers, I believe. Why, then, should they get a third of the road? (There are six lanes, recall: two currently used for moving cars (with buses mixed in), and two for parked cars.)

That is one way to look at it. Another way to look at it is that Chicago has roughly 2,800 miles of traffic lanes on arterial (main) streets, and at the moment 4 miles of (part-time) bus lanes. (They’re on the J14 line.) That is 0.1% of all arterial lanes. By contrast, 27.9% of Chicago households don’t even have a car, and 26.7% take transit to work, meaning – doing some quick math – roughly 15% of Chicagoans take the bus to work.

Here is that idea in a graph:

Meanwhile, car trips do, in fact, tend to be about twice as fast as bus trips – not including wait time – and rail trips are in that ballpark, too. This, despite the fact that between a quarter and a third of our households don’t even have cars, and that the vast majority of households are not located close enough to a train station to walk there. Buses are, in fact, the only viable transit choice for the vast majority of Chicagoans. Too often, they do suck, but they suck because of some combination of: a) we don’t know that they can be better, and b) we don’t care to make them better. But I think there are a lot of people in the city who would be interested in a bus system that we could be proud of, as opposed to felt burdened by. Why don’t we get one?