Over at Market Urbanism, Adam Hengels has written a mini-manifesto on gentrification. (In which, by the way, he graciously cites this blog. Thanks!) It’s a strong articulation of why anti-gentrification politics centered on opposing new development can’t work, though I think Adam is a bit too hasty in presenting zoning deregulation as a complete fix, or the only possible approach.

Anyway, this is his Twitter-friendly takeaway:

In the interest of time (my own and yours), in bullet points:

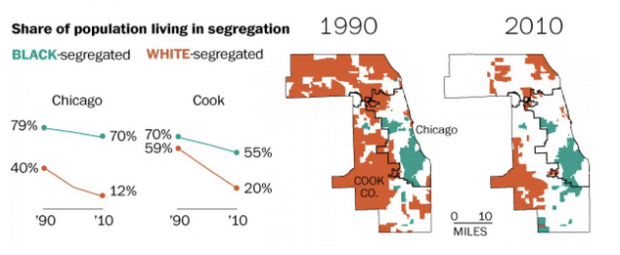

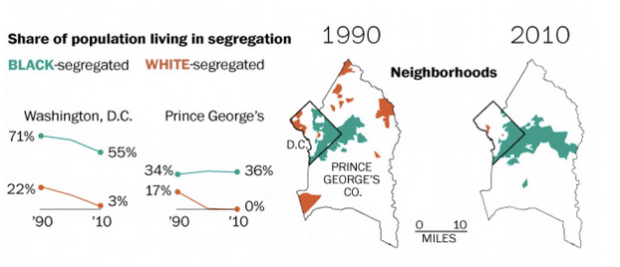

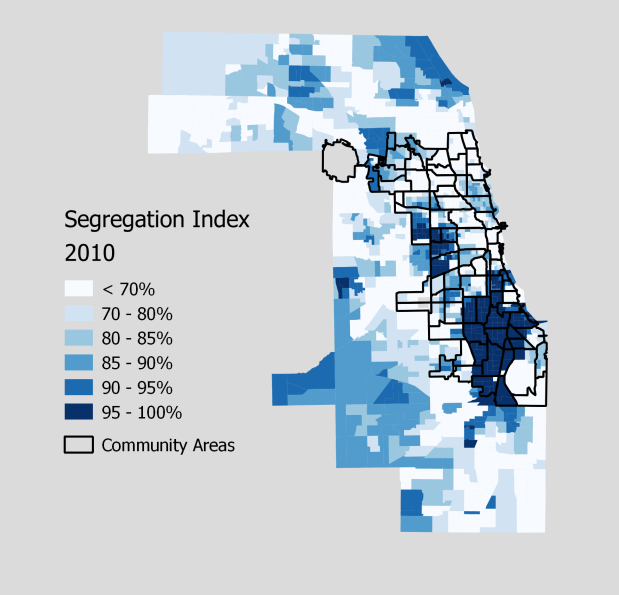

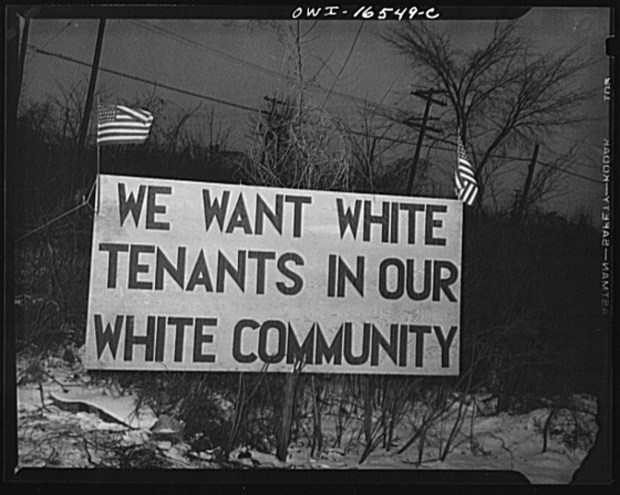

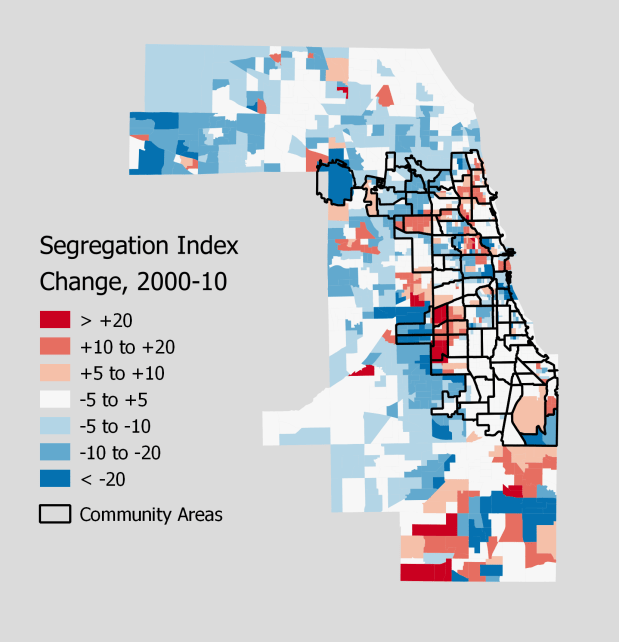

- The battlefield is both in the gentrifying neighborhoods and in the wealthy neighborhoods. The battle is also, for that matter, in the poor neighborhoods that are not being gentrified, since their gradual or rapid disinvestment sets the stage for reinvestment later on. (See the rent gap theory.) In a narrower sense, Adam is right that the engine of gentrification – that is, growing demand for housing in a system that will only accommodate that demand through rising prices – is churning both in Logan Square and Lincoln Park (or Bed-Stuy and Greenwich Village, to use a New York example). We focus on Logan Square and Bed-Stuy because they are going through a process not only of rising rents, but of dramatically transitioning social networks, from generally lower-income, mostly blue-collar people of color, to generally higher-income, mostly white-collar white people. That represents a shifting of some of the most important social-spatial boundaries that exist in American cities, and so is extremely notable. But Lincoln Park and Greenwich Village have also been changing over the past, say, 15 years – it’s just that the shift from upper-middle-class white professionals to even wealthier white professionals is a less dramatic redistricting of social geography.

Nevertheless, I don’t think it’s productive to tell the residents of Logan Square and Bed-Stuy that their observations about the changing character of their neighborhoods aren’t valid. The fact that the outcome of the Logan Square battle depends on the outcomes of other battles around the city doesn’t mean it’s not a battle.

- I think this is basically right, if by “enemy” you mean “the people with the power to change what you don’t like.” That said, again, I think it’s worth acknowledging that for people who are opposed to gentrification for reasons of culture or community, gentrifiers can be the people who are directly undermining the things you wish to preserve. Moreover, the fact that they are moving next door to you only because they can’t afford the trendier neighborhood two subway stops closer to downtown doesn’t mean that they won’t also be inconsiderate neighbors. And even if they’re considerate neighbors, it doesn’t mean that they aren’t undermining what you value just by their very presence. Which, as I’ve said before, is not necessarily a problem with a solution.

- This seems like it’s leaving some stuff out. Zoning is one really big reason why shifts in demand translate into big changes in prices, as opposed to changes in the amount of housing stock. The things that drive the shifts in demand are different. Another reason, potentially, is that housing is priced by the market to begin with. Many New York City neighborhoods have bulwarks of economic and racial diversity in the form of non-market housing, which makes up something like half the city’s units (combining public housing, subsidized housing, and rent-controlled or stabilized units).

- Again, this is one approach. Another would be nationalization (insert tongue-in-cheek emoji), or at least the large-scale removal of housing units from the market. That said, a quick evaluation of our political and financial situation suggests that such a removal is not really possible at anything like the scale that would be required. So yes, zoning deregulation really ought to happen. But that’s not exactly politically popular either, even if it doesn’t come with anything like the financial requirements of creating non-market housing. Which is to say: we need both as much zoning deregulation as possible, and as much non-market housing as possible, because we’re not likely to get anywhere close to solving the problem with either of them.

- Yes. Yes! The greatest insight of a market-based analysis of gentrification is that the actors who are given agency, who are treated as first movers in virtually all narratives about this kind of neighborhood change, are in fact pawns. They may be pawns of greater means than some other pawns, but at bottom their choices are also about constraints: Where can I be closest to my friends, potential employers, and the amenities I want, while staying within my budget? Which is why Adam’s first point, even if incomplete, is still important. In a real sense, the battle begins outside the “gentrifying” neighborhood. Mangling the old line about immigration, a gentrifier might say: We are here because they [richer people] are there [in the neighborhood where I’d rather live].