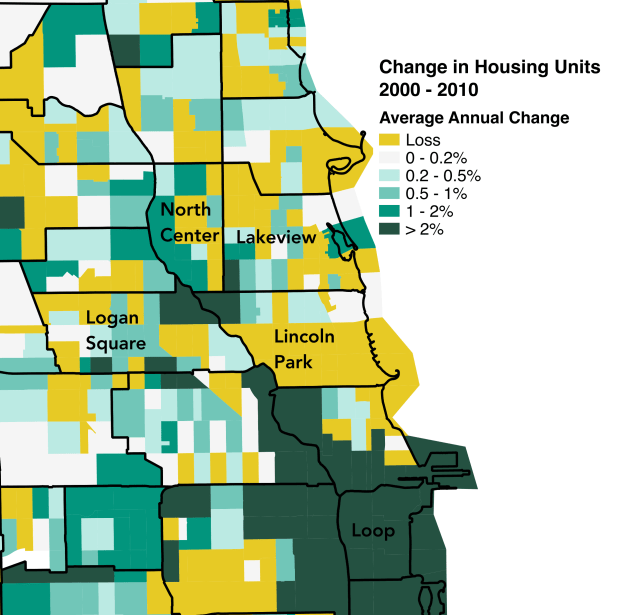

I’ve written several times about the problem of shrinking population, and shrinking housing supply, in Chicago neighborhoods that ought to be booming. A quick recap: Over the last generation or so, the number of people wanting to live in Chicago’s close-in neighborhoods, particularly on the North and Northwest sides, has skyrocketed. Many of these people are also much wealthier than the people who had been living in these neighborhoods before. Downtown, builders have responded to this situation as they had historically throughout the city: by building more densely and allowing more people to live in a given area.

But because Chicago’s zoning code fits so snugly over its neighborhoods outside of downtown – so snugly, in fact, that maximum allowed densities are frequently much lower than what already exists – builders have not been able to add much new housing. Instead, they maximize their profits by turning two-flats into luxury two-flats, or into mini-mansions for a single family. As a result, as places like Lincoln Park get more desirable than they’ve ever been, fewer people are able to live there, and its population remains about 40% below its peak, depriving the rest of the city of whole heaps of tax money that we might be able to spend on schools, roads, transit, and so on. And, meanwhile, the intensified bidding war over the housing that remains drives up prices, pushing some of the people who would have lived in Lincoln Park in 1990 to Wicker Park in 2000 or Logan Square in 2010 – in other words, it causes gentrification.

But the situation is actually even worse than that. Because the deconversion of multi-unit buildings into smaller multi-unit or single-unit buildings is just part of the removal of rental housing: there are also lots of buildings that retain the same number of units, but are converted from renter-occupied to owner-occupied. (This trend has slowed dramatically since the recovery of the rental market, and there are even a few places where condo buildings have been converted back to rental—but not nearly enough to reverse the trend of the last 20 years.)

As a result, the stock of rental homes in some of these North Side neighborhoods—which, at this point, is the market that anyone without an upper-middle-class income is in by default—has just completely collapsed.

Why is this a problem? Well, for one, owner-occupied housing almost always excludes more people—people of more tenuous economic standing—than rental housing. This is true even when monthly payments aren’t terribly different, because owner-occupied housing requires greater savings, a more stable source of income, and generally better credit. Less rental housing in that sense translates directly into a more exclusionary neighborhood.

But also, to the extent that rental housing constitutes its own market, reducing the supply of homes through condo conversions will bid up rental prices in the same way that too-low supply of homes in general will. In the wake of the recession, huge numbers of people who might in another time have chosen to buy—even people with relatively high incomes—stayed in the rental market instead. They found it much smaller than it would have been a decade or two or three before, and that almost certainly contributed to the competition for apartments that has pushed prices so high over the last several years.

And, of course, this is all happening in the context of sometimes extreme political pressure on aldermen and developers to privilege new owner-occupied housing over rentals. That makes pushing back against those pressures, as aldermen like Walter Burnett and Ameya Pawar have done, all the more crucial.