Oh, the backlog of things I want to write! To work:

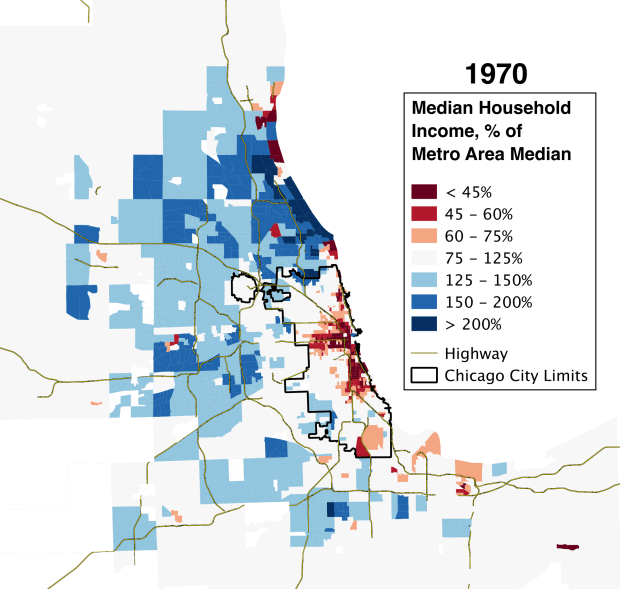

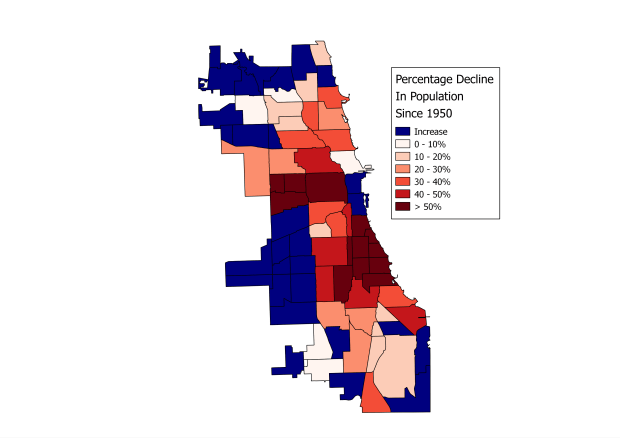

Other than “oy,” one of the most common reactions I got to the “vanishing middle class” maps I made several months ago was that focusing on the city proper necessarily missed the very important shifts occurring in the suburbs, where something like two-thirds of the people in the Chicago region live. In fact, it missed what was maybe one of the more important stories about the changing economic geography of the region over the last 40 years, which is a shift in the balance of economic power between the city and suburbs.

That’s true, so I’ve finally made equivalent maps for the entire Chicago metro area. (The researchers who provided my original data, Sean Riordan and Kendra Bischoff, made their own maps a little bit ago, and Whet Moser made some valuable graphs from their data. I’m going to use my own maps, though, from Brown’s Longitudinal Tract Database, so I can show the data in a way that’s most consistent with how I did the previous post.)

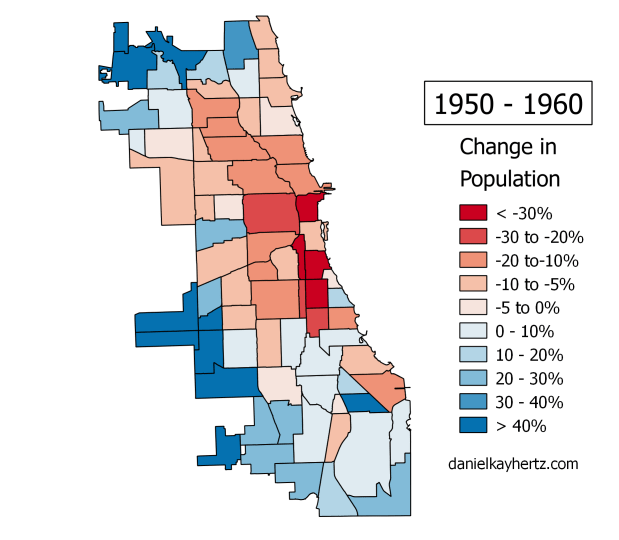

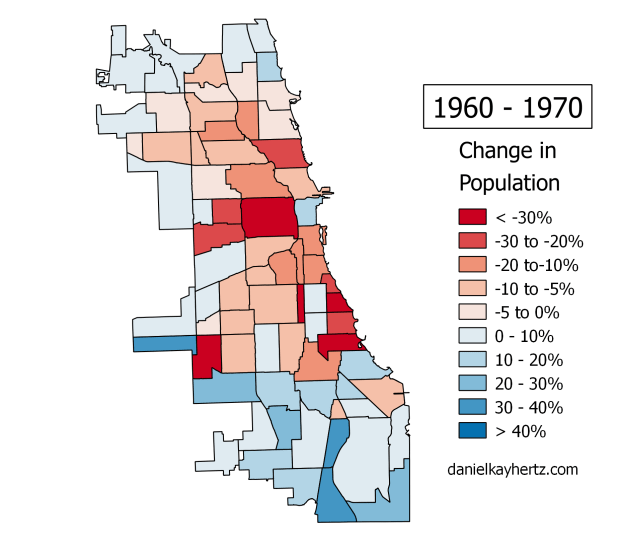

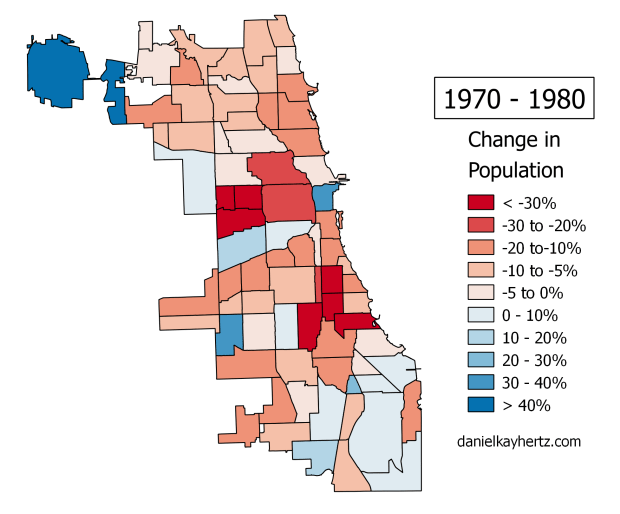

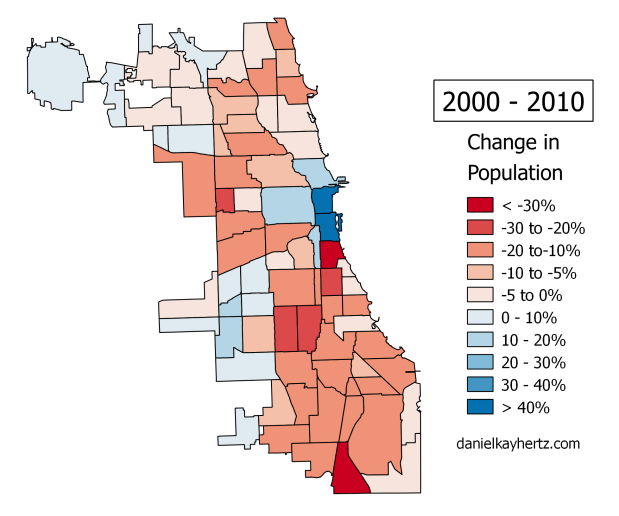

Here they are:

I think, on the one hand, that these regional maps show something very much like what Aaron Renn has described as a “new donut” pattern of urban wealth: a rich center, a ring of disinvestment, and then another outer ring of wealth in the outer suburbs. Importantly, though, I think these show that there’s nothing really “new” about this pattern – instead, the rings have existed since at least 1970, and have simply been moving further and further out from the center of the city.

Even in the first map, there’s a kernel of wealth around the Gold Coast, surrounded by extreme disinvestment, surrounded by middle-class neighborhoods, surrounded by relatively wealthy ones. In each succeeding decade, the general pattern is for the kernel of wealth to gentrify a bit of the surrounding disinvested neighborhoods; for middle-class areas adjacent to disinvestment to decline into disinvestment; for relatively wealthy areas adjacent to the middle-class ring to slip down a bit; and for some parts of the periphery to become more wealthy.

It’s a pattern that, if you’ve read Neil Smith on the rent gap theory of gentrification, makes a lot of sense. The idea is that waves of investment, disinvestment, and reinvestment in urban neighborhoods are driven by the semi-permanent nature of buildings themselves. In the beginning, say, someone builds a three-flat in a neighborhood near downtown. When it’s brand-new, it’s a highly desirable place to live, but over time, things deteriorate a bit, and newer construction further out steals away the high-income residents who can afford housing with better technology and more up-to-date styles. Importantly, the aging three-flat is not torn down or significantly renovated, because the difference between what the owner can actually charge, and what they could charge if it were a brand-new building, is smaller than the cost of demolishing the property and actually constructing a new property (or a gut rehab).

(That is: If you earn $10,000 from a building you own, and could make $15,000 if you rebuilt/rehabbed it, but rebuilding/rehabbing costs $10,000, you won’t do it. Because, you know, you’d lose money.)

As it ages, the building itself becomes less and less desirable, and so the people living there become poorer and poorer; if the surrounding buildings were all built around the same time, then something similar is probably happening in the neighborhood at large. But at some point, the calculation changes: the building becomes so low-rent that the extra income an owner could get if it were brand new is more than the cost of replacing it. (It might also be the case, of course, that the building’s rent hasn’t fallen that much more, but the value of a new/rehabbed building has increased a lot – if, say, the three-flat is in a neighborhood near other neighborhoods that have seen an increase in amenities and jobs.) At that point, since it’s profitable to do so, the owner will do a major rehab or reconstruction, and gentrification begins.

(That is: If, from the previous example, the $10,000 you’re earning dwindles to $4,000, all of a sudden rebuilding/rehabbing becomes profitable. Alternatively, if you’re still making $10,000, but a rebuilt/rehabbed building would give you $25,000 – again, rebuilding/rehabbing becomes profitable.)

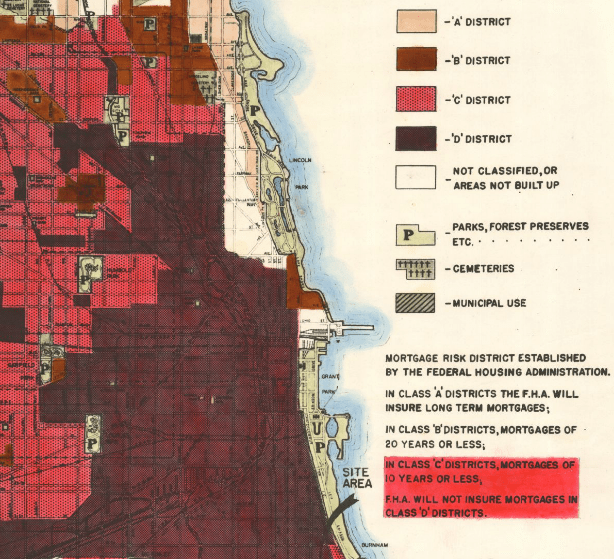

As I said, to a large extent, I think this describes what’s going on here. But anyone familiar with Chicago’s racial geography will have already noted that there’s something else, too. (If you’re not: basically all of the deep-red areas are segregated black neighborhoods. A few are predominantly Latino.) Namely, black neighborhoods seem both to suffer much faster disinvestment than you see elsewhere, and to be less able to reach the reinvestment part of the cycle. Neither of those things are news – there have been several reports about how “black neighborhoods don’t gentrify” already this year – but I think it’s particularly striking in this context. It’s not just that black neighborhoods don’t gentrify: it’s that anti-black racism is so strong that it overcomes, and arrests, the regional pattern of disinvestment and reinvestment.

Or consider the problem from a different perspective. Some people have described gentrification as a process of “racial arbitrage.” Arbitrage, more commonly, refers to someone profiting by taking advantage of the fact that the same good has different prices in different places. (For example, you might buy cheap cigarettes in Indiana and sell them at a markup in Illinois, where taxes make cigarettes much more expensive.) In this view, some disinvested neighborhoods aren’t just cheap because their housing has deteriorated; they’re cheap because most of the people who live there are non-white, which makes white people not want to live there. Since white people make up a large number of buyers in the housing market, that means demand crashes, and so do prices.

But that also means that if you’re one of the few white people who doesn’t care about living around people of color, you can save a bunch of money by moving to a non-white neighborhood of roughly equal “quality” (whatever that means for you). Each additional white person who does so, however, makes the neighborhood that much whiter – and as a result, that much more comfortable for the majority of white people. At some point, the neighborhood is white enough that most white people are willing to live there, which brings up both actual and “potential” housing prices, inviting a wave of reinvestment and more gentrification.

It appears, though, that anti-black racism is so strong that there are virtually no white (or other non-black) people willing to move into black neighborhoods, even if it means saving a lot of money. In other words, regardless of whether you think this is good or bad, racial arbitrage doesn’t work in black neighborhoods. Even in places – northern Bronzeville, say – where proximity to jobs and transportation would make you think that it would be an attractive option, there is vanishingly little evidence for it. As a result, potential rents depend entirely on the purchasing power of a disproportionately poor quarter of the population, and stay relatively low.

These two concepts – the rent gap theory and the racial arbitrage theory – are both, I think, really helpful in understanding how Chicagoland’s economic geography has changed over the last 40 years, and how it’s likely to change in the future. The foundation is a tendency for an expanding donut-shaped ring of rich and poor neighborhoods as a result of cycles of investment and disinvestment in housing. On top of that – no less powerfully – are the consequences of racism, which have a number of effects. First, they accelerate disinvestment as white people and their resources flee non-whites, and as new non-white residents are discriminated against in the provision of retail outlets, public safety, functional schools, and so on. Second, they open up the possibility of racial arbitrage: that is, another way for “potential rents” to rise and attract reinvestment and gentrification. Third, for black neighborhoods in particular, they can freeze an area in the disinvestment phase by acting as a sort of ceiling on potential rents.

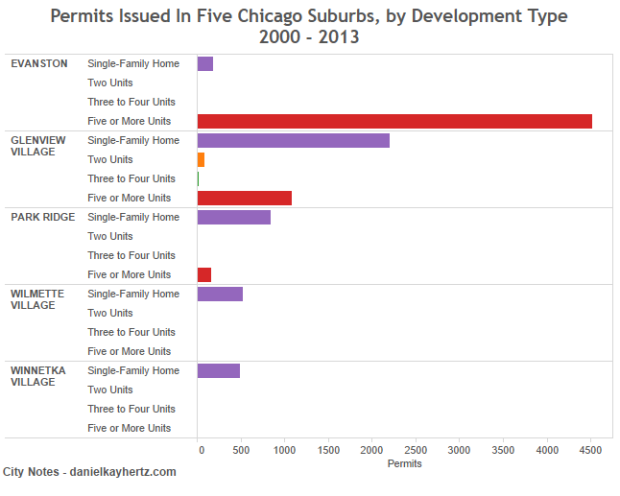

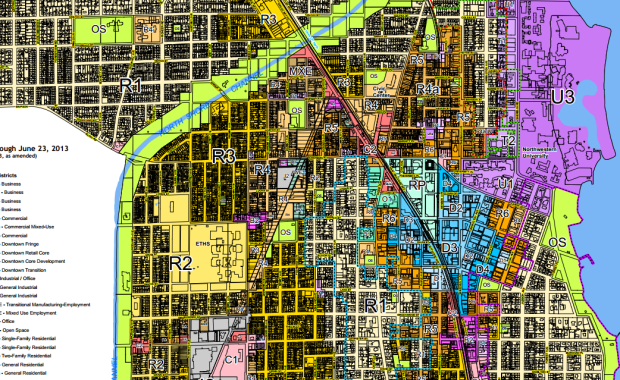

Finally, of course, zoning laws can act as an accelerant on the reinvestment/gentrification phase by effectively capping population in neighborhoods where lots of people would like to live, forcing some of those people to move to adjacent communities, and raising actual and potential rents there.

There’s obviously quite a bit more to say about all this; hopefully I’ll find the time to do so soon, and hopefully I’ll also hear from other people who have thought of things I haven’t. But, as I’ve said before, neighborhood change is easy to experience – and is too often talked about – as a kind of capricious, unpredictable thing. In reality, it appears that it’s heavily influenced by certain patterns and rules. To the extent that we’re unhappy with what neighborhood change looks like, understanding those rules, so that we can change them, seems important.