This is too good not to make a separate post: commenter Neil, or “nei,” on some of the historical differences in racial segregation between NYC and Chicago. Read it first. I add a few thoughts at the end.

Talk to Me Like I’m Stupid is working!

***

I’m going to a add a few comments on NYC that might be insightful even though they’re a bit of a nitpick. First, I’m not sure if this a good assumption:

But in New York, black neighborhoods have become significantly mixed, in particular with people of Hispanic descent.

You’re assuming those neighborhoods were entirely black at one point and then hispanics came later for some reason. I don’t think that’s a good assumption, I’d guess they arrived at roughly the same time. Large-scale migration of hispanics into NYC started mainly in the 50s, and was mostly Puerto Ricans, looking at wikipedia numbers it looks like the Puerto Rican influx was slightly earlier than the black migration, which continued into the 60s and later. The poorest Puerto Ricans settled in the some of the same areas as blacks. The South Bronx was roughly equally hispanic (Puerto Rican) and black around 1970, today it’s about 2/3rds hispanic but with a more diverse mix of hispanics. The housing projects also become dominated mainly by blacks and Puerto Ricans, though some projects are mostly blacks and others mostly hispanic, though I suppose. Hispanics average significantly lower income-wise than blacks in NYC, and NYC Puerto Ricans tend to below average income-wise among NYC hispanics, I’d guess Puerto Ricans were poorer than blacks then, too. Unskilled, discriminated against with the added difficulty of a language and cultural barrier. The many that had little money moved to the cheapest and worst neighborhoods the city had to offer, which often had a large black population. In many ways, back then, it makes sense to group hispanics and blacks together, especially pre-1980. But…

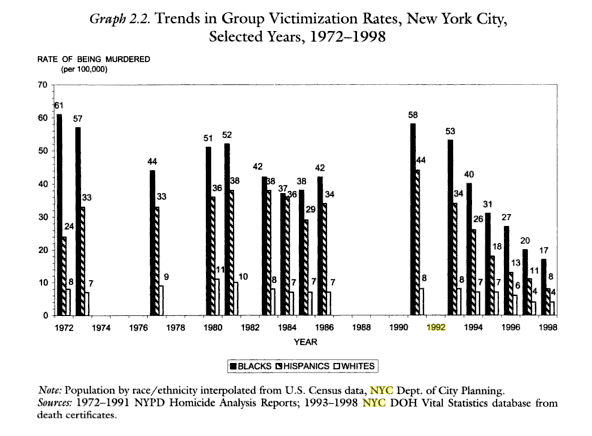

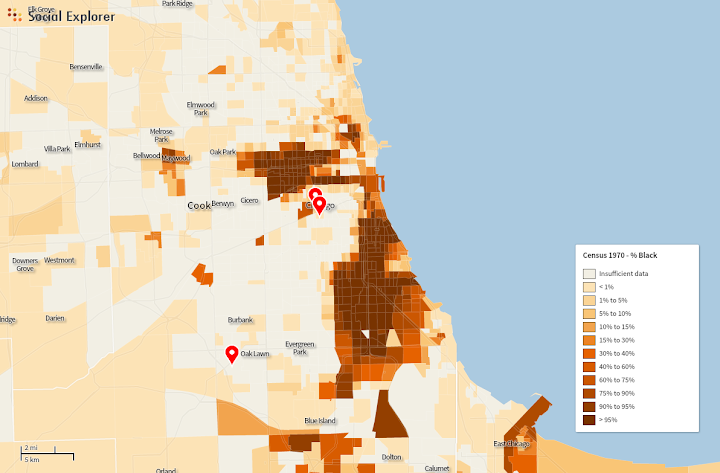

It appears blacks triggered faster “white flight” than Puerto Ricans. Many Puerto Ricans lived amongst blacks, but there were many more mixed white & Puerto Rican neighborhoods than white & black neighborhoods. For example, Williamsburg, Brooklyn pre-gentrification was mixed Puerto Rican and white (mainly Italian-American); still has some Puerto Ricans left. I think there were a number of other similar neighborhoods, but not so many stable mixed white-black neighborhoods. If you look at sites with old maps by race, such as socialexplorer.com (you’ll need the professional edition), the black population was far more concentrated than the hispanic population. Looking through by decade, you can see census tracts near a black neighborhood shift from mostly not black to mostly black. Want to guess which neighborhoods would have a quick decrease in white population? Check the black population map a decade before, areas adjacent would lose whites. Hispanics weren’t as segregated, which suggests that white flight was more of a racial than just an economic thing. Violent crime rates were higher among the black population, but in the late 70s/early 80s the hispanic/black difference was small, suggesting both populations were equally “ghettoized” in some sense, but fear of blacks seemed to cause more white flight than fear of hispanics.

Hispanic Murder rate dropped more than blacks, probably partly from heavy immigration starting in the 80s onward as well dismantling of drug gangs. 2011 rate was 1.4/100k for whites, 5.9/100k for hispanics, 14.6 for blacks and 1.5 for Asians.

Here’s a screenshot of a map of black population in NYC, 1970 [didn’t take a screenshot of a similar map for hispanics]

Chicago looked very different in 1970:

both from socialexplorer. It appears the equivalent of the South Bronx in Chicago in the 70s/80s would have been entirely black, rather than mixed black-hispanic. From what I can tell “white flight” in NYC came in two types:

1) Sudden very quick transformation from mostly white to minority. Usually more often from an influx of blacks then hispanics, and occurred in the poorest white neighborhoods, but generally mainly by near an increasing black population (block busting). Usually had white flight in the 60s or early 70s. South Bronx, Northeast Brooklyn are the best examples.

2) Gradual decrease of white population, starting later maybe in the 70s. Younger generations of whites slowed moved away, I heard them being described as “grandma neighborhoods”, since the non-transplant whites are older. They have often have some white population left, and a large immigrant population, but almost no black people (sometimes every possible race besides black). Southern Brooklyn and a lot of Queens are good examples of these places. While they were majority white, blacks were often discouraged from moving in by implied threats of violence.

Here’s an odd pattern. The three blackest zip codes in NYC are actually well off by city standards.

Top on the list (zip code 11411) has a median income of $81k/year, median home price of $404k. 93% black, 38% foreign born. Random streetview:

My guess is it’s too expensive for poorer hispanics (mostly owner-occupied homes), and whites or middle-class hispanics see little reason to move there, while some middle-class blacks want to move to a nice black neighborhood. Of course it was white at one, a bunch of synagoues in the area stand out as an odd relic, a couple have been bought by churches. Again, the white flight must have racial rather than economic as it’s not really any poorer than white neighborhoods in that area of Queens/Nassau.

The black population of NYC has a large immigrant contingent, but instead of black immigration breaking down segregated neighborhoods, it helped keep their setup. Since 1980, the black population has had a large domestic out-migration with the black numbers balanced by black immigration (mainly from the Caribbean but also from Africa). I saw numbers saying in 2000, 40% of NYC’s black population was either foreign born or had one foreign born parent. Most black immigrants moved to existing black neighborhoods, keeping the same segregation pattern. One interesting exception is some neighborhoods in Queens, there’s a section that’s mixed asian-black-hispanic. The largest black area of NYC [Northeast Brooklyn, with a larger black population than South Side Chicago] hosts the West Indian parade annually (maybe the city’s largest parade).

There are a number of neighborhoods in NYC that experienced white flight that have no black people. Sunset Park, Brooklyn has few white people, it had large-scale white flight around the time of de-industrialization around 1970. Puerto Ricans replaced the exiting whites, but no blacks. Today, western half of it is hispanic (mix of Puerto Rican and Mexicans), the eastern half is Chinese. The switch between the two groups happens in about a block, it’s a bit jarring. Continue east further, and it’s almost entirely Hasidic Jewish (Borough Park) with another quick transition. Almost no blacks today in any of those places. Washington Heights switched from White to Dominican rather quickly, you have it labelled as <10% black, though it has plenty of black hispanics.

***

Daniel again: It actually occurred to me when I was writing the original post that I didn’t know when the integration of blacks and Hispanics happened in NYC, and I’m glad someone set me straight about that. It’s an interesting point, although there has to be a much longer and more complicated story about why they ended up together: I guess maybe the lateness of arrival of Chicago’s Hispanic community? Or were Mexicans (the largest Latino group in Chicago, by far) less inclined to live in black neighborhoods than Puerto Ricans for some reason? Or were New York’s black neighborhoods somehow more attractive?

I did know about New York’s black community’s large foreign contingent, which really doesn’t have a parallel in Chicago. Chicago’s Caribbean and African immigrants are much fewer, but they also tend to move to the North Side’s small black communities in Uptown, Edgewater, and Rogers Park, rather than the main segregated black neighborhoods on the South and West Sides. I don’t think there are any segregated black community areas in Chicago that are more than one or two percent foreign-born.

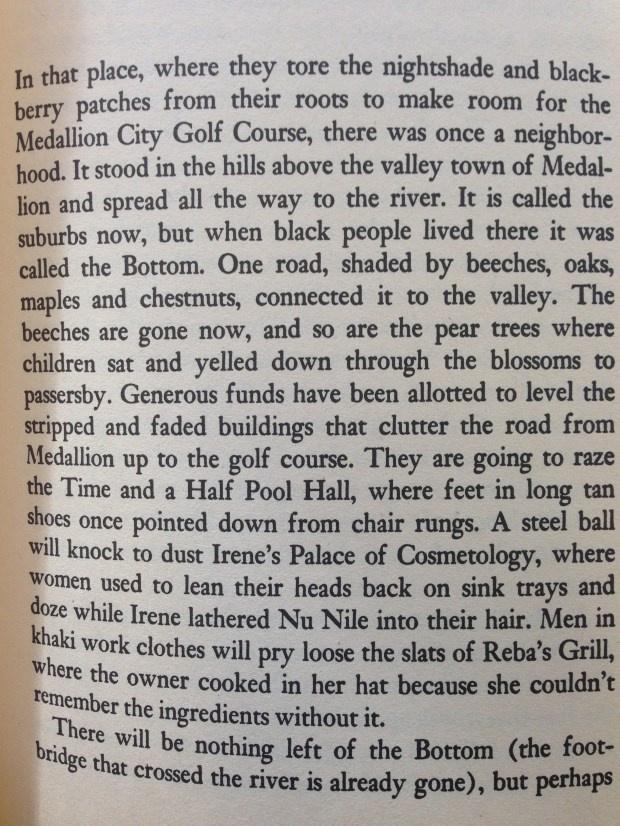

In other ways, this description is very applicable to Chicago.

The distinction between rapid and slow white flight, for example – although the vast majority of cases with black neighborhoods were rapid, there’s been some slower white flight – and lots of “Grandma neighborhoods” – on the Southwest Side, where Latinos and Asians have been replacing whites for ten or twenty years.

The distinction between “racial” and “economic” white flight, I’m not sure I fully endorse, but it does complicate the narrative somewhat to point out the places where black newcomers actually outranked their would-be white neighbors economically, but the whites left anyway. That also has a few parallels in Chicago – Calumet Heights, I believe, and a few other places on the far South Side – places that are solidly middle class, but are still shunned by non-blacks.

Anyway. Thanks, Neil, for this.