A letter published last summer in the Chicago Tribune asked for a second look: “When you see us coming, you might hurry and get in your car and lock your door. Then speed through these streets at 60 mph like you’re on the highway, trying to get out of this ghetto. [But] we want you to know us.”

The authors were a class of fifth graders from the South Shore neighborhood, just a few miles down the coast of Lake Michigan from the University of Chicago. Like many Rust Belt communities, South Shore has its share of problems. But it also has ornate Jazz Age apartment blocks and large, stately homes; it has skyline views from its beaches, and the brilliant ballrooms of the Cultural Center, where Barack and Michelle Obama held their wedding reception. By express bus or commuter rail, it’s just over half an hour to downtown jobs.

If South Shore were in New York or DC, in other words, it would be exactly the type of place you’d expect to be suffering from too much attention, rather than too little.

But just a few weeks after the Tribune letter was published, two Harvard researchers confirmed statistically what many residents had known, or suspected, for a long time: in Chicago, black neighborhoods like South Shore just don’t gentrify.

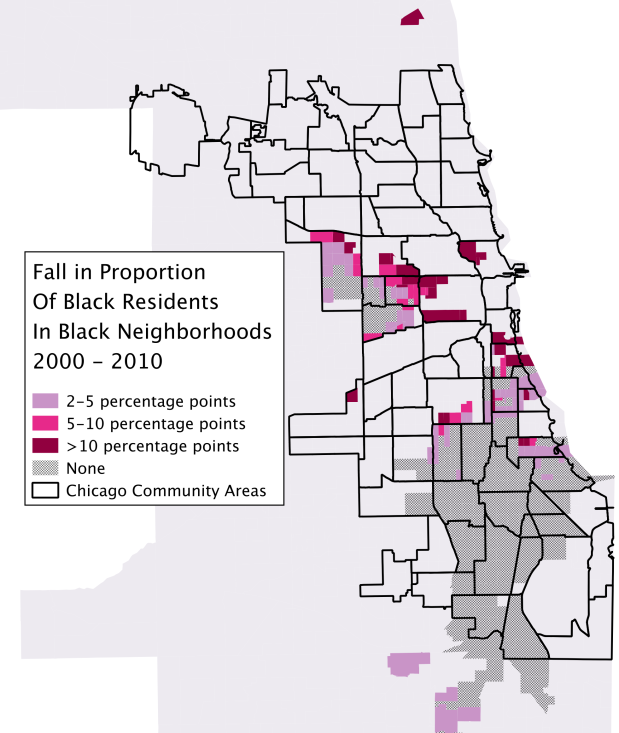

In fact, it goes much farther than that: they don’t undergo any kind of ethnic change at all. Robert Sampson, one of the researchers, coined the term “white avoidance” to describe the phenomenon of whites simply refusing to move to neighborhoods where more than 40% of the residents are African-American. (Though it’s worth noting that there are actually quite few Chicago neighborhoods at that 40% level: most have either small African-American populations, or are over 90% or 95% black.) But Chicago’s rapidly growing numbers of Latino and Asian-American residents have been steering clear, too. Between 1980 and 2000, the only majority-black neighborhoods to see significant integration were Cabrini-Green – where a major public housing project began transitioning to mixed-income developments that included high-end condos – and the South Loop, whose train yards, warehouses, and convention centers presented more of a blank slate for redevelopment than a cohesive neighborhood.

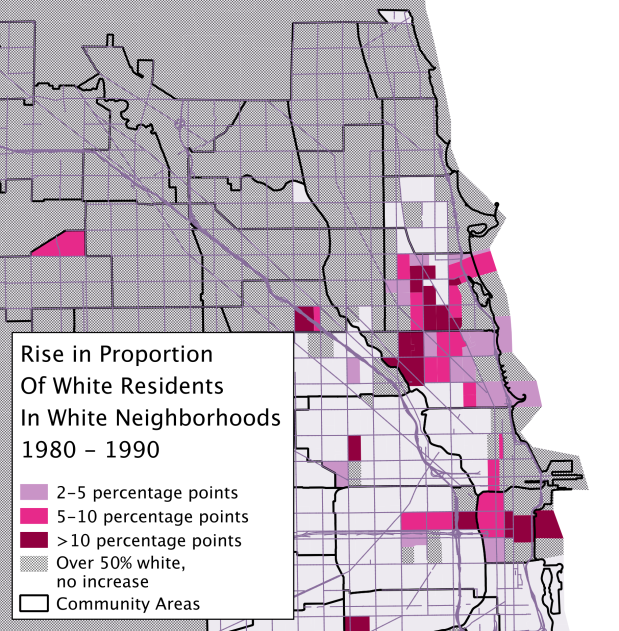

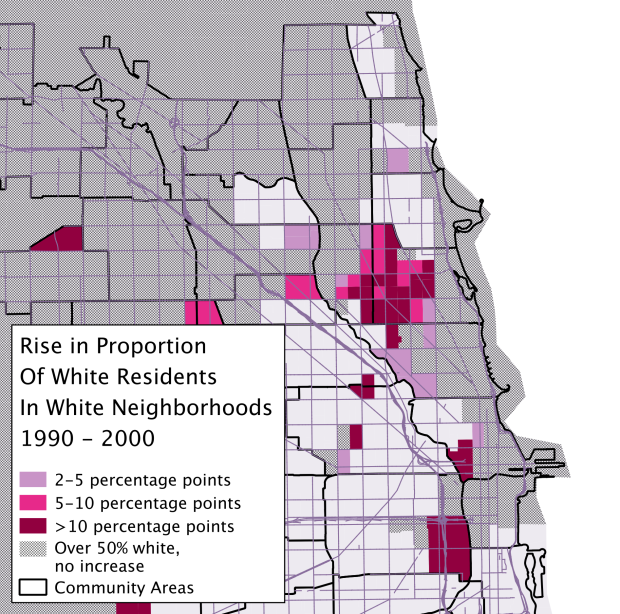

At the same time, Chicago’s white neighborhoods underwent a profound racial transformation. The far Northwest Side neighborhood of Jefferson Park is typical. In 1980, it was as homogeneously white (97%) as South Shore was black. But by 2000, nearly one resident out of five was a person of color. By 2010, that was up to almost one in three.

These trends – demographically frozen black neighborhoods and rapidly integrating white ones – changed a city that had been profoundly and neatly segregated into one defined by asymmetrical segregation. While Asians, Latinos, and whites are far from perfectly mixed, there are many neighborhoods where they live together. For black households, on the other hand, ethnic isolation remains the rule.

On both counts, though, those trends may be changing.

Since 2000, for the first time in Chicago’s history, people of other ethnic backgrounds appear to be moving into black neighborhoods in nearly every region of the city except the far South Side. To be clear, in many cases the change amounts to just a few percentage points of a neighborhood’s overall population: notable only because the previous rate of change was zero. But dramatic transformations in other places began with a trickle, too. If one of the cardinal rules of residential migration in Chicago is actually weakening, it may open up the possibility of broader demographic change across the city’s South and West Sides in the medium to long term.

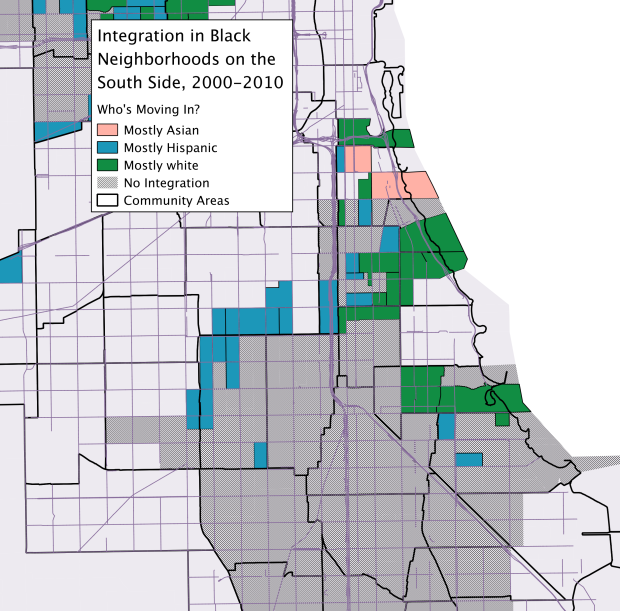

Moreover, the changes are much more complex than the familiar narrative of white-led gentrification. As often as not, the newcomers are Latino or Asian-American. Not surprisingly, this seems to depend on the demographics of the neighborhood next door: on the West Side, where black communities bump up against Mexican and Puerto Rican districts to the north, these new residents are mostly Latino. Northern Bronzeville, close to Chinatown, has a rapidly growing Asian-American population. And the communities around Hyde Park – a racially mixed neighborhood with a large number of white residents – are, in fact, getting slightly whiter.

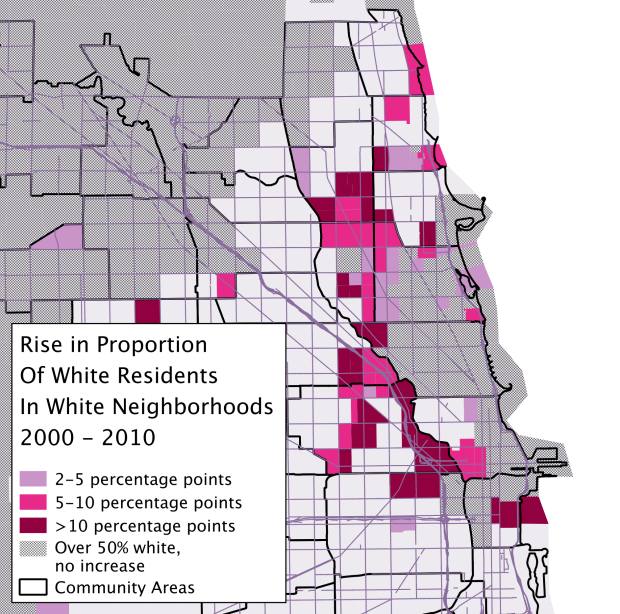

But while Chicago’s black neighborhoods take a few tentative steps away from extreme segregation, some of the city’s white neighborhoods are moving in the opposite direction. Over the last 30 years, as a broad swath of the North Side has gentrified, it has also become disproportionately white. It now seems that nearly as many white North Side neighborhoods are becoming more segregated as are becoming less – a dramatic reversal from recent trends.

At first blush, this seems like a contradiction: why would some parts of the city be getting more segregated as others become somewhat more integrated? Most likely, however, they’re both part of the same broader phenomenon.

For the last few generations, Chicago’s economic geography has resembled a growing donut. In the center is a small, but quickly expanding, core of wealth. As the core grows, a surrounding ring of low-income neighborhoods gets pushed further out. And those neighborhoods, in turn, elbow aside a suburban ring of wealthier communities, which also move away from the core.

For various reasons, including the racial income and wealth gaps, neighborhoods that get absorbed into the rich core become much whiter, explaining the growing segregation there. But as that disproportionately white sector expands, it also helps to push the residents of neighborhoods in its path further out – and, in some cases, into black communities.

Still, that’s probably not the whole story. Ethnic communities, from Poles to Mexicans, have been moving increasingly far from the city center for many generations; only recently have some of them ventured into black neighborhoods. While research like Robert Sampson’s shows that “white avoidance” remains a powerful force, other academics have found evidence that white tolerance for black neighbors has (very slowly) inched up over the last few decades. That might also help to explain the sort of very tentative integration along the boundaries of black neighborhoods that Chicago is now experiencing.

It’s harder to guess at whether these trends – if they grow and continue – are likely to make a famously unequal city a bit more just. Of course, the increasing racial and economic segregation of the core is a huge problem. Would declining segregation in historically black neighborhoods provide a counterbalance? Maybe. But longtime residents who have grown accustomed to living in a neighborhood with a particular community and culture have every reason to be wary of losing those things. And particularly where the newcomers are white – mostly along the borders of Chicago’s growing wealthy core – gentrification may eventually become a reality, and integration may be a passing phase.

Perhaps the most promising trend, then, is the movement of Latinos and Asian-Americans into black neighborhoods – particularly ones that have been losing population as residents move to the suburbs or southern cities. For many shrinking white neighborhoods around the Rust Belt, Latino and Asian immigrants, and their American-born children and grandchildren, have brought a much-needed economic and demographic shot in the arm. If black neighborhoods in Chicago can enjoy those benefits too, it may provide a path towards community development that doesn’t require rapid gentrification.

At the moment, of course, this all remains conjecture. A few bricks may have come loose from the structure of Chicago’s segregation, but the fortress remains. It will be a very long time before it’s gone.