tl;dr

In Chicago, aldermen often set zoning to be more restrictive than the kind of development they eventually plan to approve, so as to maximize their negotiating power.

But there’s a loophole: all residential zoning, no matter how strict, allows single-family homes.

So developers looking to avoid negotiation can just build (very expensive) single-family homes.

The downzoning-as-negotiating-tactic ends up leading to more single-family homes than aldermen (or local residents) actually wanted.

That’s a problem on a number of fronts: affordability; public resources; transit; climate change; and so on.

If we’re going to move towards a system in which every development has to be negotiated, then that rule should apply to single-family homes as well as apartments and condos.

In the most naive version of the story, zoning is a quasi-objective, quasi-scientific endeavor. Planners, in consultation somehow with the public or their representatives, assign every plot of land in the city a code that denotes the kind of uses, and intensity of uses, that are appropriate to undertake there. They determine “appropriate” according to some sort of rational set of criteria: putting denser uses closer to major transportation corridors and nodes of activity; keeping “incompatible” uses, like factories and homes, apart; and generally respecting the existing built environment.

Of course, at least in Chicago, you don’t have to poke the zoning apparatus very hard before this story falls apart. With the exception of the immediate area around downtown, Chicago does not allow more density in many of the places that planning textbooks would tell you it should go: near transit stations, for example. (Yes, we have a “transit-oriented development” law, but it’s mostly about parking requirements. It only gives a modest density bonus to parcels that are already zoned relatively densely.)

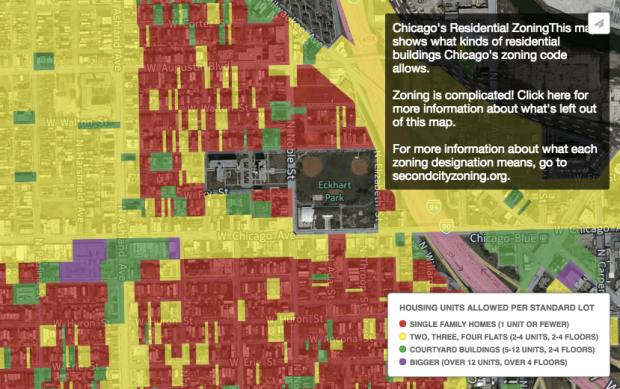

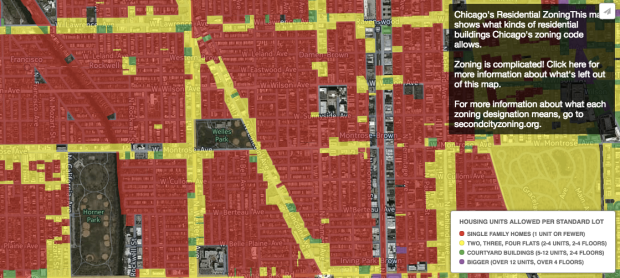

And while Chicago’s zoning code mostly keeps factories and residential homes apart—though not always, as the above map shows; that vertical corridor of uncolored land is a manufacturing district in the middle of a residential neighborhood—beyond that, it often fails miserably at even pretending to be keeping incompatible uses apart. Remember, theoretically, each zoning category is different enough that it ought to be “incompatible” with every other category; otherwise, the authors of the code would have just combined them. That’s not to say they can’t be relatively close—say, commercial with apartments above on a main street, and residential-only on the side streets nearby—but it would be ridiculous to have a bunch of different zoning categories hopscotched around the same blocks.

Except Chicago does that all the time. Above, you have a checkerboard of single-family-only districts (red), small apartments (yellow), larger apartments (green), and even a smattering of very dense apartments (purple). And while the densest category is only found near the corner of Chicago and Ashland, two major streets, the other three categories are liberally sprinkled around the very same blocks on the very same side streets. In many cases, “zones” make up just one or two buildings, surrounded on all sides by other, supposedly incompatible, zones!

There is a word for this: “spot zoning.” It is generally illegal.

But whatever. Maybe the issue is an overzealous application of the “existing built environment” criterion. After all, Chicago’s side streets were usually built as a haphazard mix of single-family homes, small apartment buildings, and larger apartment buildings. If we just zoned each parcel to the category closest to its current building, then you might end up with something very much like the above map.

Except that’s not how we do it, either. The block above happens, at least, to be consistent in its zoning: it’s all single-family only. But literally none of the existing buildings—which, by the look of them, have been around for well over a century—are single-family homes.

Nor is that at all unusual. Every building in the above scenes is also zoned to be single-family only—anything else would be, according to law, “incompatible”—despite the fact that none of them depict any actual existing single-family homes.

So what’s going on?

Well, an alternative theory would be that instead of zoning being the result of a professionalized, semi-scientific process of analysis, it’s instead the result of politics. In particular, local politics, since in Chicago zoning changes controlled virtually entirely by the ruling alderman.

And who controls the local political process? Well, over at City Observatory, I covered the debate between two theories. One, the “growth machine,” basically posits that local politics are dominated by business and development interests, which manipulate zoning to overbuild, relative to what an “objective” observer might think appropriate. On the other side, there’s the “homevoter hypothesis,” which suggests that local politics are dominated by homeowners, who are mostly interested in maintaining the value of their homes. As a result, they’ll make zoning that leads to underbuilding, so as to reduce the number of “competing” sellers and avoid other neighborhood changes that might risk reducing property values.

If these are the options, which wins? Well, the study I wrote about at City Observatory, which was based on zoning changes in the 2000s in New York City, found that in places where you might expect it would be most valuable to build—areas near high-performing schools; whiter neighborhoods; neighborhoods seeing high home price appreciation and population growth—there were many more zoning changes to allow less density than to allow more density. That’s really hard to square with a growth machine story, but fits in perfectly well with a homevoter hypothesis story.

And what about Chicago? Before even looking at the city at all, you would probably expect that Chicago would be closer to the homevoter hypothesis than New York—simply because there are way more homeowners here (the homeownership rate is about 45%, rather than 35%).

But beyond that, and without doing a whole study, I can make an observation that makes me lean towards the homevoter hypothesis here, too: while there are abundant examples of neighborhoods where current zoning allows less density than the prevailing built environment—that is, for example, it’s illegal to build a three-flat on a street full of three-flats—there appear to be vanishingly few parts of the city where zoning allows more density than the prevailing built environment. Since intensifying land use is basically the guiding philosophy of the growth machine, a situation in which very little land is allowed to have its use intensified as of right seems hard to square with that sort of regime.

(There are two exceptions. First, areas with lots of vacant land often have zoning that allows reasonably dense buildings as of right, which you could reasonably claim would be “intensifying.” But for one, there’s generally very little building going on in these areas, and I suspect the arrival of construction would result in a flurry of rezonings; and two, if the goal of the “homevoters” is to increase their property values, getting rid of vacant lots makes a lot of sense. The other place where lots of intensifying is allowed is downtown. I think there’s a longer story to tell here, but I also would probably concede that much of downtown is, in fact, ruled by the growth machine.)

But there’s another thing. Which is this:

Via @Aldertrack, how zoning in Chi works now: create artificially restrictive district to maximize aldermanic power. pic.twitter.com/pqdY0LeuS2

— Daniel Kay Hertz (@DanielKayHertz) November 18, 2015

Politics are not only about constituents. They’re also about actual officeholders. And if you’re an officeholder, regardless of what your constituents want, you probably want maximum flexibility, and maximum leverage, in any given situation. In Chicago’s “planning” environment—that is, where all zoning changes are controlled solely by the local alderman, and where zoning changes can be made by that alderman very easily—that means there’s a massive incentive to downzone so that every potential developer will have to negotiate with the alderman. In the best possible interpretation, aldermen do this to allow public meetings where neighbors have the opportunity weigh in on exactly what they’d like to see built on every single parcel as developer interest arises, and then act on those wishes. In a less generous interpretation, aldermen do this to allow public meetings as a show of democracy, placating local voters while expecting things to end up basically as they would have anyway. In the least generous interpretation, you might note that this creates an incentive for developers to, say, give campaign donations to any aldermen whose wards include land they’d like to build on, since they’ll need aldermanic approval for every single project.

But even if we stick to the most generous interpretation, there are a few problems.

First, by moving planning from a theoretical planning department in City Hall to the local alderman’s office, they have shrunk the pool of voters who are consulted about changes from (theoretically) the entire city, with perhaps an extra weight given to people nearby, to only the people who show up to a given community development meeting. Without going into a whole spiel about the issue of hyper-local planning, I’ll just say that excluding many of the people who are affected by decisions about housing from having a voice in those decisions is a recipe for problems. (If this doesn’t make sense in the context of, say, Logan Square, imagine who doesn’t get a voice in hyper-local community meetings in, say, Lincoln Park.)

Second, while it’s not necessarily bad to allow negotiations over land use—you get a bit of extra density in exchange for another design concession, or less height, or more greenery, or whatever—it might be better to have these negotiations at the level of a neighborhood plan, rather than parcel by parcel. That’s both because of the “who’s enfranchised” issue above, and because negotiations require a lot of everyone’s time and effort. The smaller the payoff, the less inclined people will be to expend that time and effort. Meaning, in this context, that you might just shut out smaller developments—three flats, say—altogether, with developers deciding it’s only worth going through a whole community process if they’re proposing much larger buildings.

Finally, there’s a huge loophole: single-family homes. While in the story above, Alderman Burnett is downzoning to disallow all residential (even though, as he says, he only expects residential proposals, of which he will eventually grant one), much of the time, the alderman downzones to RS-3, which only allows single-family homes. In fact, there is no residential category that does not allow single-family homes as of right. Which means that big expenditure of time and effort can be avoided, if you’re a developer, by building single-family homes rather than apartments or condos.

If you’re inclined to be against density for the sake of being against density, then maybe that’s a feature, not a bug. But if you’re concerned about anything else, it’s a huge problem. Affordability? Basically all new single-family homes are going for the better part of a million dollars, and significantly more than units in a multifamily building in the same location. Plus, single-family homes won’t trigger the city’s Affordable Requirements Ordinance, so there won’t be any below-market units, either.

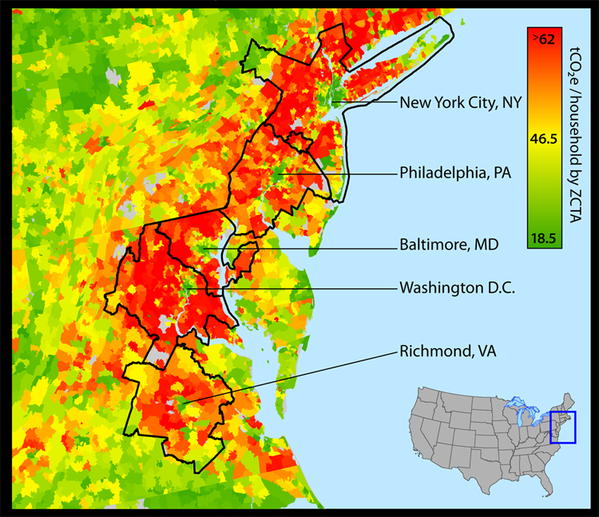

Transit? Allowing only single-family homes in central urban areas reduces the kind of density that supports bus and rail lines, leading to a vicious cycle of declining ridership and service.

Public services? Single-family homes will generally create less total property value than multifamily buildings, with smaller property tax bills to support vital city services.

Climate change? Less population density means more carbon emissions per capita.

Local businesses? Single-family homes mean fewer people within walking distance of local business districts. That sort of population decline may be a big part of why there are empty storefronts in some of Chicago’s most affluent neighborhoods.

Now! None of this is to say that I think we should outlaw single-family homes. I don’t.

But it does seem to me that these are, together, a good enough reason to believe that the single-family loophole is a problem. Remember, the issue is not that we’re zoning land for single-family homes because we think that’s the only “compatible” use, but because it gives us maximum negotiating leverage over the appropriate multifamily building we eventually want to approve. And yet, in the process, we’re giving developers a huge incentive to build less densely than we think is appropriate, which exacerbates all the issues above.

So basically what I’m saying is that if we’re going to move towards a system where every development is negotiated—where, in planning lingo, basically everything is a mini-planned development—then we should require negotiation for single-family homes as well.