Jordan Fraade asks:

He then gives three good places to start: the Democratic Socialists for America-Los Angeles statement against Measure S; a short piece by Torrie Fischer on YIMBY socialism; and Rick Jacobus’ excellent column in Shelterforce last year.

As far as a sort of programmatic, what-do-we-do-now agenda, I think Jacobus pretty much has it covered. His big points:

- At the regional level, every piece of evidence we have suggests that additional housing absolutely helps to hold down the growth of housing prices. Growing regions that want to avoid big increases in the cost of housing need to build more housing.

- At the neighborhood level, the relationship is much more ambiguous. There need to be counter-market tenant protections because we can’t count on supply to balance demand in any particular location.

- Modern rent control seems not to have serious harmful side effects, but it also is only middlingly helpful in preventing displacement.

- So creating a large and growing stock of housing whose price is not set by the market—whether publicly or privately owned—is also important.

But I’m interested in exploring how Jacobus (or I) got here: what sort of left principles bring us to these conclusions, and where might we have made different decisions?

I’m going to start from what I think of as a kind of “soft socialism,” in which our default position is not to regulate a given economic activity, but our belief in egalitarian outcomes and in the tendency for markets to be coercive and destructive means we have a light regulatory trigger.

I’m also going to assume that treating being housed as a basic right is uncontroversial, and so government stepping in to provide assistance to whoever the market has left homeless (or severely rent-burdened) is a given.

Who, exactly, a truly free housing market would leave unhoused is an interesting question (about which I went around with Salim Furth, Stephen Smith, and others recently on Twitter), but is sort of unhelpful for the purposes of this post.

So instead let’s assume that the market optimists are right, and that basically everyone with a full-time job would find affordable housing in every metropolitan area if only housing supply weren’t restricted by zoning laws that prevented new construction and banned traditional affordable housing strategies like boarders and conversions of single units to multiple units. And let’s assume that people who can’t work, or can’t find work, are provided for, either with some kind of housing voucher or public housing. And let’s also assume that we can all agree on regulations to assure basic building safety and sanitation standards.

What, then, would be the progressive justifications for additional housing regulation? I can think of a few things:

Land is a quasi-monopolistic, unearned source of wealth and driver of inequality

One reason to regulate is that even in a mostly laissez-faire environment, urban housing isn’t infinitely producible, and it certainly isn’t infinitely producible in a given location, and some locations are much more valuable than others, and people who find themselves in possession of land in the more-valuable location are therefore in a position to earn economic rents on their quasi-monopoly housing.

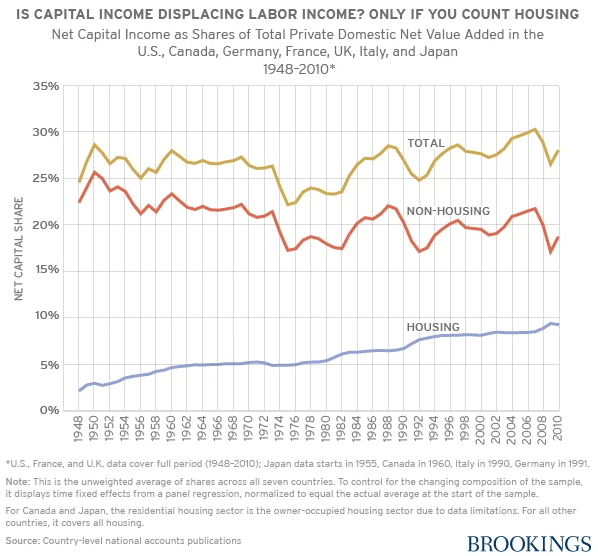

Moreover, as cities and economies grow, valuable urban land tends only to get even more valuable, and so housing ownership can be a major driver of wealth inequality. In fact, this seems to be the case in the real world.

Of course, this isn’t really an argument for regulating the production of housing: In fact, the restrictions on construction that exist are only making housing in those locations more monopoly-like, and increasing inequality. But it might be an argument for seizing the unearned wealth that urban housing ownership generates, which you could do either with a confiscatory land value tax, or a kind of vast public community land trust.

Integration

Even if a free housing market could produce adequate affordable market-rate housing for all employed people, it’s extremely unlikely that it would produce adequate affordable market-rate housing for all employed people in all neighborhoods. And since public goods and public services like safety, jobs, schools, parks, and so on are to some extent provided locally, even a sort of loose “equality-of-opportunity” liberalism would be concerned about geographic segregation, either economic or along some other sort of line of privilege like race.

Of course, this is also generally not an argument for restricting the production of housing: the evidence suggests that more restrictive zoning is associated with more segregation, not less. (And history suggests that is, more often than not, its intended purpose.) But it’s an argument for either more targeted subsidies, or public housing, to create a stock of low- and moderate-income housing in neighborhoods where the market won’t.

The moral right of occupancy

We also might believe that housing stability, the ability to choose not to move, is so important to many people—both in pragmatic ways related to the logistics of daily life, as well as in deeper, more sense-of-self-related ways—that we would want to prevent the market from forcing people to leave their homes, even when other affordable housing is available elsewhere.

This is also not an argument for restricting housing production per se, but it might have that effect if it prevents would-be developers from clearing tenants out of older buildings they want to redevelop. More directly, it may be an argument for some kind of rent control or targeted housing subsidy to people with quickly rising housing costs—or a guaranteed right of relocation to public housing in the vicinity of your old home.

Community stability

Beyond a concern about the housing stability of individuals, we might be concerned about the stability of communities.

This could take a number of forms. A loose version—a desire to allow social networks to keep their physical proximity to each other—might be satisfied by protecting each individual member of the social network, and so nothing beyond the section above would be necessary.

But a stronger form of community-based protections might be concerned about more than just the physical proximity of individuals. It might, for example, hold that for certain definitions of community, the built environment must be preserved as an important piece of the community. It might hold that a certain institutional environment is necessary, and therefore require restrictions on businesses and other local establishments. Most radically, it might hold that the community requires not just the presence of its members, but the absence of non-members—or at least, limited numbers of them.

These communitarian concerns are the ones that are most likely to call for restrictions on new housing. They’re obviously far more complex than my summary here, and in some cases—particularly the exclusion of non-community members—they open the door to profoundly troubling policy, and are on questionable (though not indisputable!) ground as policy informed by left principles. Though the word “community” is thrown around quite a bit in housing debates, specific rights to housing are generally put in individual terms. I think in many cases, though, the logic is communitarian, and further elaborating these ideas and principles could help shed light on why people end up where they do on questions of neighborhood development.

Of course, this is very far from an exhaustive list. I hope other people can add to it, or respond and critique it!