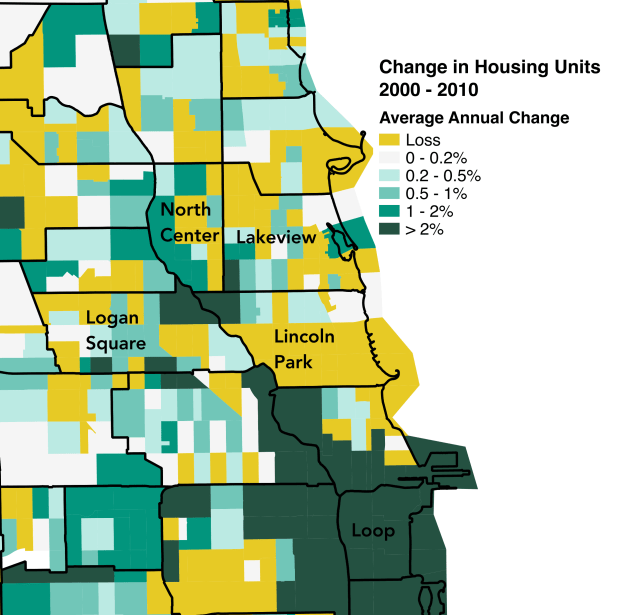

One of the most under-appreciated aspects of Chicago’s housing system – although, thankfully, it’s becoming more well known – is how radically the city restricts the kinds of housing that can be built in the neighborhoods. Forms of housing that are traditional all over the city, and that provide subsidy-free affordable housing for working class people, are illegal nearly everywhere outside of downtown and the lakefront. In fact, the vast majority of Chicago neighborhoods are zoned so that the only legal form of new housing is the single-family home – which in many places will necessarily be out of reach for moderate-income people. This is true even in neighborhoods, and on streets, where two-flats, three-flats, and other apartment buildings already exist. Essentially, we’ve imposed classic suburban exclusionary zoning in North Center, West Town, and elsewhere.

But it’s hard to visualize these restrictions, because they come in the form of incredibly arcane and detail-laden laws that no one ever reads, and couldn’t understand if they did. One way that I like to get to the bottom line of what the zoning code means for housing is to measure the number of housing units allowed per standard 125′ by 25′ city lot. That strips away all the various design issues and gets down to a basic measure of density: how intensely can this land be used? By (roughly) how many people?

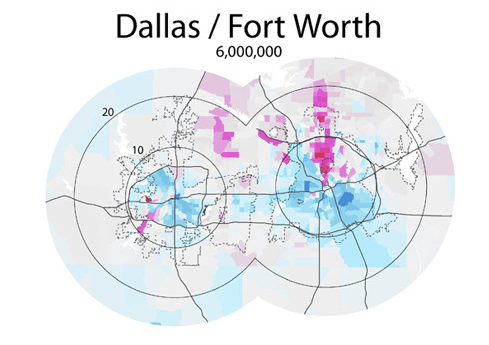

So, in the interest of zoning readability, I’ve made an interactive map that shows how many residential units are allowed by the zoning code in any given place in the city. Look up your block! Look at streets around L stations! They’re mostly zoned very, very tightly.

Now, because this is so simplified, I feel the need to make a few caveats. First, if you’d like to get some more details about what these zones allow, but in a more readable format than the actual city code, go to Second City Zoning. Second, here are some things you should know before you use the map:

1. The Simplified Chicago Residential Zoning Map is residential. That is, it doesn’t show zoning in places that only allow non-residential uses, and it won’t show non-residential uses on lots that allow both. Especially along major streets, many zones allow, say, one residential unit above a storefront. If you see that a lot is zoned with a code that begins with B or C, you can mentally add “stores” to the list of uses allowed, in addition to however many residential units.

2. Zoning in Chicago is extremely ad hoc. In practice, that means that virtually every sizable development involves a zoning variance or planned development process that goes beyond the zoning you’ll see on the map. In one sense, that’s good, because it gives the zoning code some flexibility; on the other, it means that development doesn’t follow any kind of plan, and each new development must relitigate the battle over density with the neighbors. That deters an enormous amount of construction – especially the sort of small-bore densification that should be the bread and butter of a healthy city. A developer working on a 200-unit project is going to make enough money to justify going through several public meetings over the course of months; someone who just wants to build a four-flat on a single-family-home-zoned parcel is probably not.

3. Not all units are created equal. Depending on other regulations in the zoning code – height, floor area ratio, parking – as well as, of course, the market, a new building might be made up mostly of studios or three bedroom units. Unit size, in turn, will obviously determine how many people live in each unit, and thus the whole building. So it may be that a 10-studio building has fewer people than another building with four three-bedroom units.

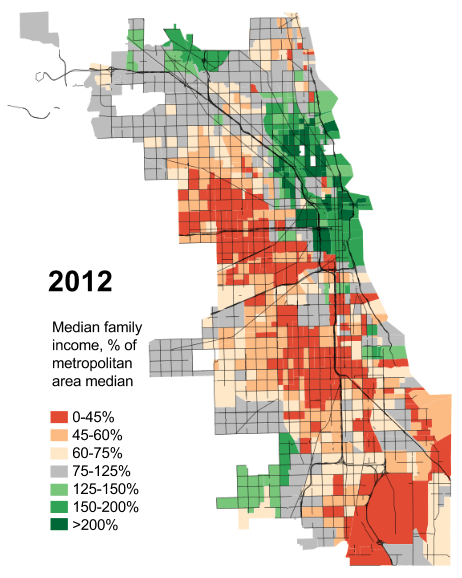

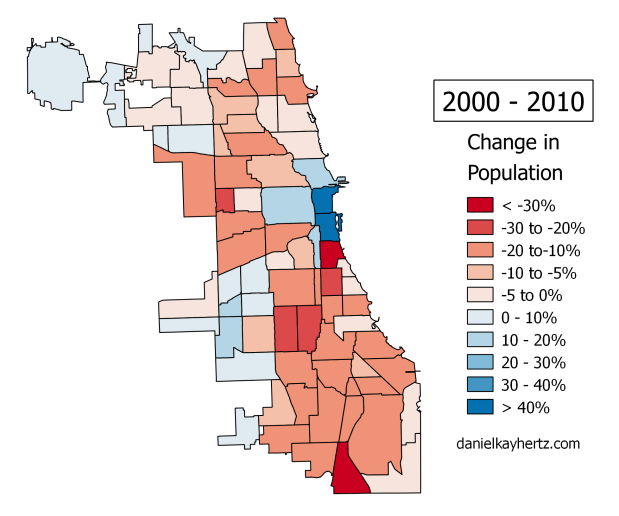

4. It’s interesting to note which parts of the city aren’t tightly zoned, outside of downtown. Mostly, it’s black neighborhoods on the West and South sides. Of course, with the exception of parts of Bronzeville, there isn’t enough demand to warrant new construction in most of these places anyway – but that, I would like to suggest, is part of the point. It hasn’t come up. Historically, downzoning on the North Side has followed the arrival of denser building.

I think that’s it. Enjoy!