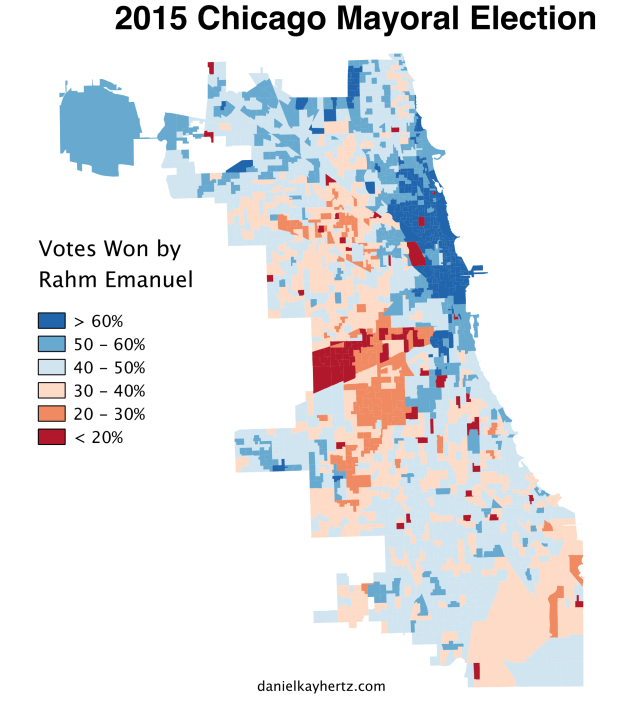

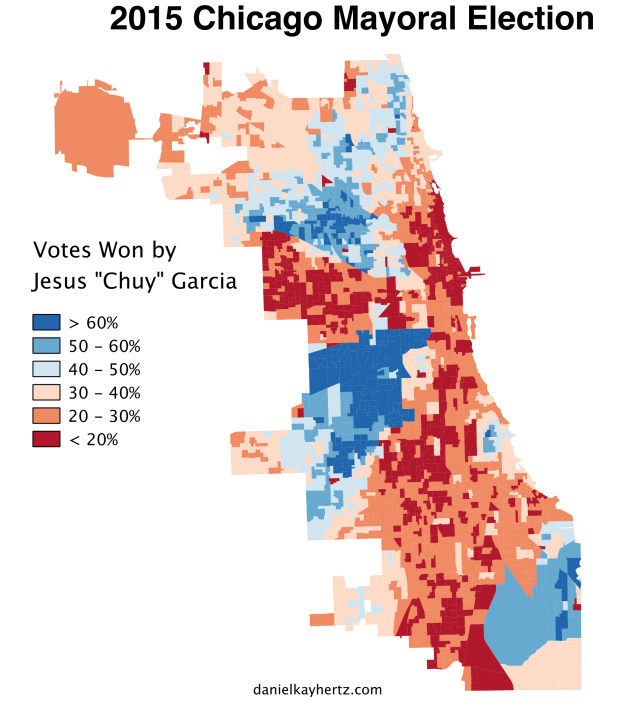

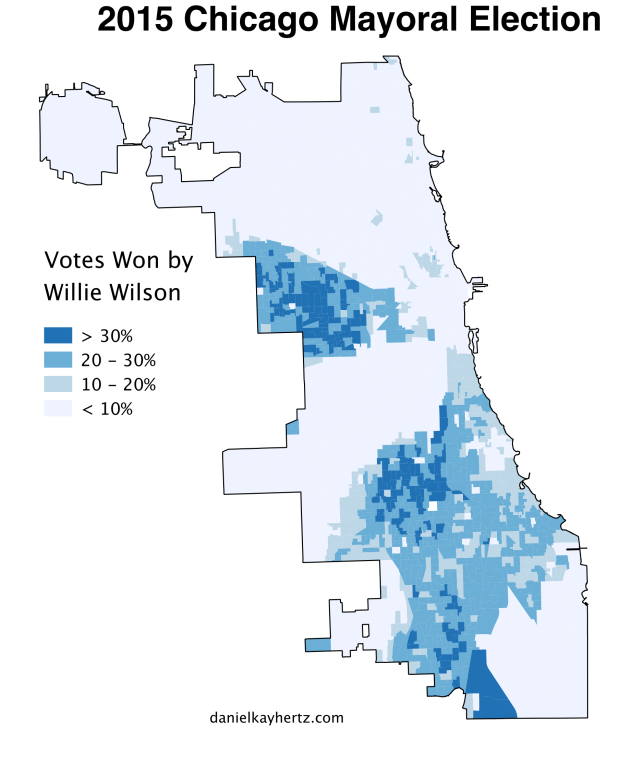

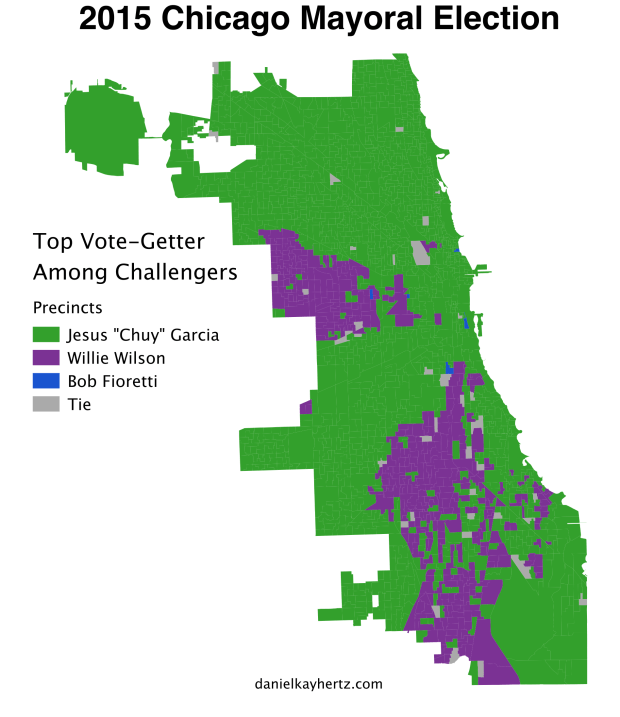

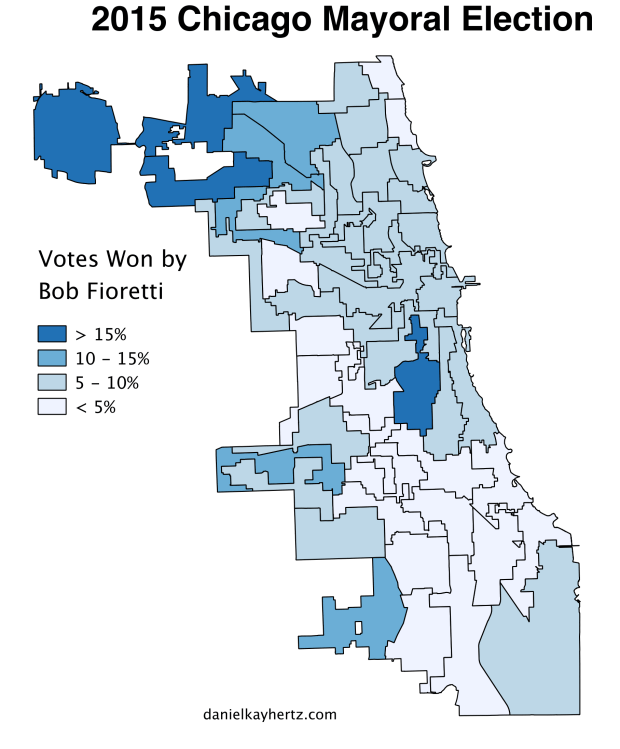

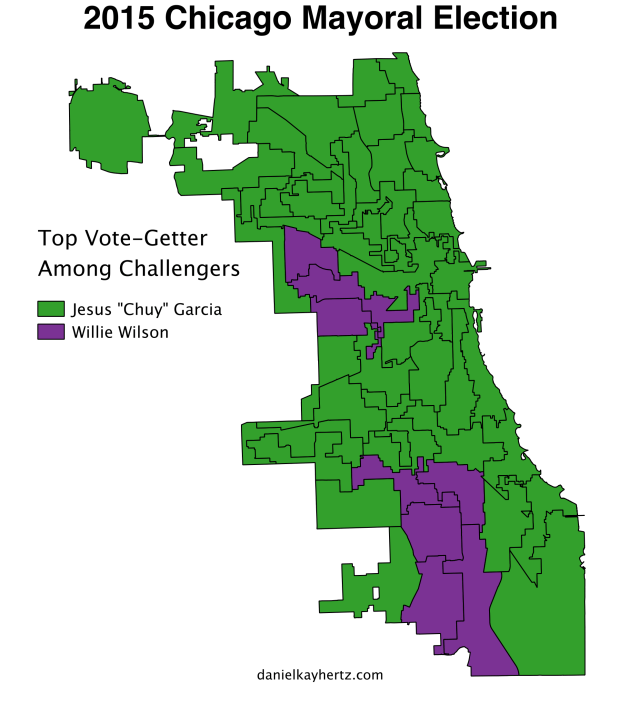

These are by precinct, rather than ward, and so provide a lot more granular detail. I’ve kept all scales and colors the same, except where new categories were required (because Fioretti won a few precincts, but no wards, for example).

Category Archives: Uncategorized

We had an election, here are some maps

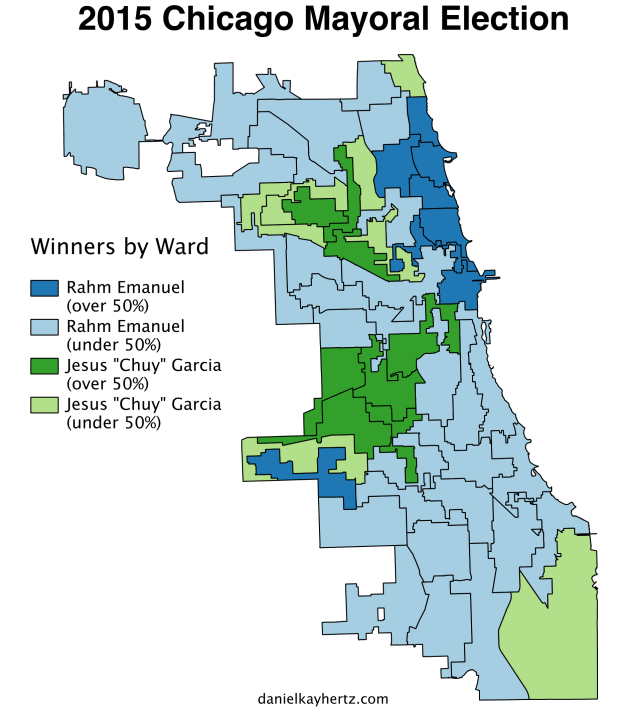

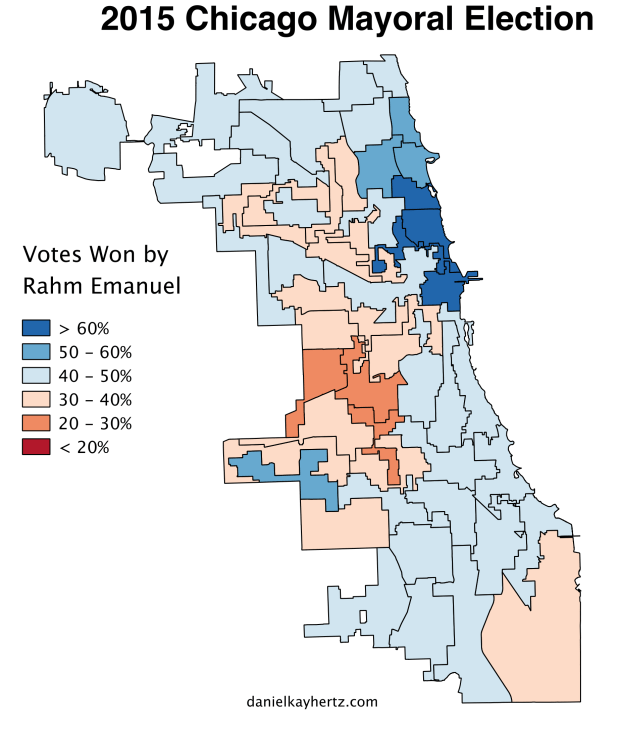

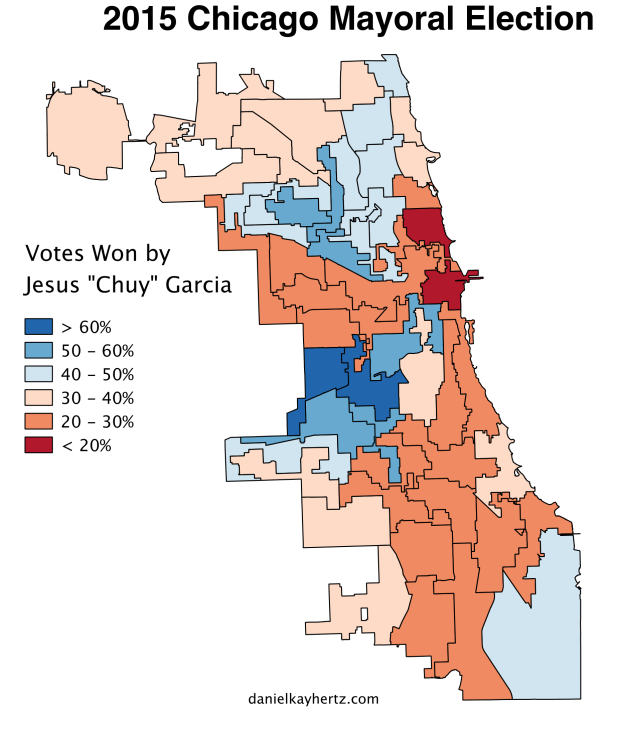

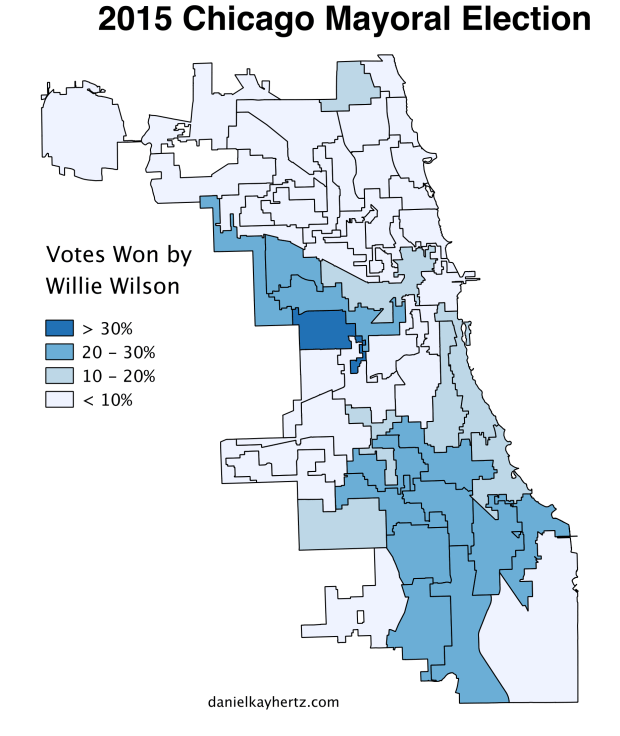

UPDATE: I redid these maps with more detail, by precinct, here.

Here are some maps (here is another map):

Two fun things to do

First of all, Streetsblog Chicago – which, on a shoestring budget, regularly produces some of Chicago’s best reporting on urban transportation – is holding a fundraiser to buy new shoestrings and resume publication after a brief budget-related hiatus. It’s next Thursday the 29th, in the form of a pedway bar crawl with Moxie, the LGBTQ urban planning organization. It meets at 5:30 at Infields, in the basement of Macy’s on State Street.

Without Streetsblog, many of these stories simply won’t be covered anywhere. If you’re at all free, I’d love to see you there. If you can’t make it, consider pitching in electronically! Streetsblog Chicago is a fucking valuable thing, and we shouldn’t just give it away for fuckin’ nothin’.

Also, less importantly, I’m going to be speaking on a panel with the lovely Yonah Freemark and Pete Saunders about neighborhood change at UIC’s Urban Innovation Symposium. We’ll be speaking on Friday the 30th from 12:00 to 12:45 in the Lecture Room at Gallery 400, 400 S. Peoria. Come if you want!

2014

This blog, and all the people I’ve met through it, have been an unexpected highlight of my year. Thanks, everyone. I’ve included a few of my favorite posts and articles below, in case you want to get on top of your 2014 blog reading nostalgia early.

Happy new year.

Ten Posts

February 24: “Why Is Urbanism So White?”

March 21: “Chicago’s Housing Market Is Broken”

March 31: “Watch Chicago’s Middle Class Vanish Before Your Very Eyes”

April 14: “How Segregated Is New York City?”

August 5: “Things That Are True About Crime in Chicago”

August 8: “The Dignity of Fifth Graders”

August 25: “The South Side: Not Actually an Unmitigated Sea of Misery”

September 18: “Nationalize Manhattan”

October 21: “Buses: They Don’t Have to Suck”

December 5: “Chicago’s Growing Income Donut”

Six Articles

February 20, CityLab: “Blame Overbearing Government for Gentrification, Not Just Neoliberalism”

April 23, CityLab: “There’s Basically No Way Not To Be a Gentrifier”

August 13, Washington Post: “One of the Best Ways to Fight Inequality in Cities: Zoning”

October 20, Next City: “How Metra’s New 30 Year Plan Could Reshape Chicago Regional Rail”

November 20, Washington Post: “Urban Neighborhoods Are Getting More Diverse. But What Are They Losing?

December 12, Next City: “Chicago Rethinks Rules for Affordable Housing”

Chicago Urbanist Calendar

So during an otherwise lazy weekend, I’ve finally launched a minor project I’ve been thinking about for months: the Chicago urbanist calendar. (There’s also a link to it up at the top of the page.) Basically, I am in a near-constant state of agitation as a result of missing events I’d like to go to because I only hear about them after they happen. To avoid that – and as a gracious public service – I’m now collecting all potentially interesting urbanist-related Chicago events in a public Google calendar, and hosted on this blog. The events range from governmental meetings that are open to the public, to civic hack nights, to architectural tours, to university panels on housing and gentrification; I’m trying to err on the side of including too much, rather than too little. To that end, if you or anyone you know is involved with any events coming up soon or in the more distant future – or know of an organization that regularly or occasionally puts on events that should be on this calendar – let me know! You can either email me (danielkayhertz [at] gmail), or leave a comment on the calendar page. (I won’t publish the comment, but I will add it to the calendar.)

Alternatively, if you have any ideas for how to make the calendar better or more useful, let me know! Hopefully this is something that will get refined over the next few months.

Maybe one day Chicago will not waste its billions of dollars of transportation infrastructure, but until then, have this Next City article

Service innovations like increased frequency don’t yet appear anywhere in the strategic plan, and a Metra spokesperson confirmed that the agency has no plans to move in that direction. In August, Streetsblog Chicago reported that one board member flatly rejected that kind of service expansion, claiming that running a single extra train during rush hour would cost over $30 million. (Aikins, however, reports that GO Transit spent just $7.7 annually to adopt half-hourly frequencies on its two biggest lines.)

FYI

On Tuesday, March 18th (next Tuesday!), I’m giving a short talk about why land use law is ruining your life. It’ll be at the Open Government Hack Night at 1871 in the Merchandise Mart in downtown Chicago at 6:00 pm, and I believe (?) there’s gonna be food. Much of the source material is from the blog, but there will be a few new data projects and maps I’ve been working on, too.

You should come! So far I have met only two blog readers I didn’t already know before I started writing, and I’d love to meet more. Plus, you know, there’ll be food.

The Blog in Brief

Cleaning out my Feedly “Saved for Later” folder:

1. I take issue with two recent Greater Greater Washington posts.

First, I’m not actually sure I agree with either the framing or substance of this post about BRT. Maybe it helps for planners or self-defined urbanists to think of BRT as a collection of features, rather than a package, but I think that’s just confusing for the public at large, and it makes it way easier for cities to “cheapen the brand,” as it were, by calling something “BRT” that’s really just signal prioritization or some such tinkering. If I were the head of a transit authority, or a think tank, or writing an influential blog, I think I would try to promote the idea that BRT is, in fact, a package of features that together deliver about as good a transportation service as you can get without actually putting vehicles either underground or on an elevated structure, way cheaper than any train technology. The CTA has stumbled around on this, but eventually found its way to my position: its Jeffery Jump line, which has half-mile stations but dedicated lanes only in peak direction during rush hour and no pre-paid stations, was initially billed as BRT, but now CTA officials take pains to call it “BRT light.” Good on them for that.

GGW also writes:

Even worse is what happens when all the tools in the box are used at the same time—what enthusiasts laud as the “gold standard” that resembles a “subway in the street.” If buses are to carry subway-like passenger volumes, traffic lights and pedestrians can’t get in the way. Gold-standard BRT becomes an interstate-like highway through the city, what urbanists have been fighting since the 1960s.

Except that virtually nowhere in the U.S. are any bus lines likely to carry “subway-like passenger volumes.” The demand just isn’t there; even in Chicago, the Ashland BRT is only likely to carry around 45,000 people a day. But, yes, BRT does require relatively wide avenues with relatively fast-moving traffic. That’s a feature, not a bug. If we choke crosstown surface transportation, we’re reducing people’s access to the amenities, jobs, and other people that are the very raison d’etre of big cities. Not every street in a major city can be optimized for pedestrians with narrow, traffic-calming dimensions.

The other GGW post that made me go “huh?” is this one, claiming that what the DC Metro really needs is to visually differentiate its stations by taking a cue from LA, which does things like put fake palm trees and film reels at its Hollywood station. Supposedly this is because a) people can’t tell one station from the other, which is making them confused, and b) subway stations should be bright and colorful to reflect the joy that is life.

A + B = yuck

But look: visual cues like palm trees will only register with people who know to associate that with a given station, and those people will already know how to get around. Everyone else is going to take way longer to go through the thought process Giant Fake Film Reel –> We Must Be At Hollywood than they would to just read a sign that said, “Hollywood,” or listen to the driver say, “This is Hollywood.” And as for aesthetics – well, yes, the Moscow subway is truly a subterranean palace, and although I’ve never been there, it looks like LA is doing a good job making their stations inviting, too, in a very different way. But ideas like painting Harry Weese’s honeycombed ceilings blue or orange according to the line that runs there just make me want to gag. It’s a matter of taste, of course, but DC has what is recognized by a good number of people to be one of the most architecturally significant subways in the world. The people who think its aesthetics are grim are unlikely to be swayed by a coat of paint, and they would be right. Make the lights brighter and add signage, if necessary. Don’t try to make it something it can’t be.

(Note that this principle should have been applied to Chicago’s renovated Red and Blue Line subway stations, which might have been restored to a somewhat-less-stark-than-Weese Art Moderne aesthetic, but which instead were slapped with a hodgepodge of more “popular” styles that at best clash with the vestiges of the originals, and at worst look like one long tiled bathroom wall.)

2. At its worst, urbanism as a subculture seems to combine the humorless self-righteousness of activist politics, the impersonal spreadsheet thinking of dataheads, and the bloodless management-speak of business schools. At its best, of course, and at all sorts of points in the middle, it is much more attractive. But even so, I appreciate the attempt by the Wannabe Urbanist to inject a bit of the humanities, or its sensibility, into the conversation.

I’m not sure that what we really need is more sentences like “Question anyone who uses the term urbanism: does their usage reinforce the dominant forces of capitalist urbanization?”, but I do think that passages like this are a breath of fresh air in the face of urbanist triumphalism:

[F]or regular people, urban living in modernity is about absorbing and adapting to changes often out of our control, and negotiating the practical and emotional consequences….

It is easy to get caught up and distracted by the spectacle of urbanism, the glittering megastructures and brand-name architectural projects; it is just as easy to be seduced by the tactical urbanists and neo-Jacobsians into thinking that if we (and be we, I of course mean the urbanists who clearly know what is best for our cities) all just got together with shovels, we could build the bike lanes and curbside seating areas that would solve all these problems.

The point I am trying to articulate is that the experience of modern urban living is not a set of images; it is the difficult project of being ourselves in cities whose form and function are controlled by forces of capital, whose interests rarely align with those of any other party.

I think that last part actually does the rest a disservice, by limiting the point to the influences of capital. The larger theme is a very powerful one that’s very underdiscussed: the experience of living in a city is terribly humbling for anybody who is remotely honest with themselves. The forces beyond one’s control, whether that’s some other person or collection of persons, or some systemic force that’s not really under anyone’s control, are overpowering. It is challenging both on the level of daily subsistence, and on an emotional, even existential level. Who do you belong to? What do you belong to? The overlapping circles of in-groups and out-groups and territories and allegiances and relationships are almost literally never-ending. Suppressing all those tensions from the conscious mind is possible, I suppose, but they’re always there, and they certainly inform how we feel about the way a city ought to work, and what it ought to look like. It would be nice if the urbanist conversation brought that to the surface every now and again.

Also, points for bringing up the sensual experience of cities, which is especially on my mind right now as I’m reading James Baldwin’s Another Country, a book that makes love to Manhattan on every second page, and claws at its eyes on every fourth.

Questions for Richard Florida, one month late

1. Why, in these graphs, are we comparing wages minus housing costs to…housing costs? It’s certainly interesting that greater real estate prices are so positively correlated with white-collar wages that those workers end up with greater take-home income in high-housing-cost metros, even after subtracting those housing costs. But wouldn’t the better comparison – if your question is whether the concentration of college degree holders in certain metro areas is good for non-college degree holders in those same metros – be after-housing-cost wages for non-college degree holders versus the percentage of white-collar workers in the labor pool? Maybe the results would be the same; but it would be nice to see.

2. Even better, given that metro areas with high housing costs tend to be older cities with solid public transit systems, what do those graphs look like if you chart wages minus housing costs and minus transportation costs against the percentage of white-collar workers in the labor pool? As the Center for Neighborhood Technology has shown, including transportation costs in the “structural costs” of a given metro area gives a very different picture of the burden on low- and moderate-income families than looking at housing alone. (Of course, the tendency of elite cities to be transit-friendly isn’t necessarily inherent to the phenomenon of talent clustering – except that much of this conversation is about using urbanism to attract college-educated workers. Given that, it seems relevant whether the current urbanist model of lower transportation costs and higher housing costs does, on net, hurt blue-collar discretionary income.)

3. This is outside the immediate scope of your project, maybe, but how do these effects vary by metropolitan area? What is the relationship between talent clustering and blue-collar well-being, on the one hand, and restrictive zoning (which has been shown to artificially raise real estate prices), or economic segregation? Are there extremes where, even according to your original models, an increase in white-collar workers is good, economically, for blue-collar workers – say, in a very poor, tax-base-thin city like Detroit?

Answers, hopefully to come!

Speaking of Houston: Two Links

The Atlantic Cities has a longish essay on the limitations of “density” as a goal for urbanists, which attempts to answer some of the questions I posed about the value of density per se versus traditional, walkable urbanism that may be less dense. (I apologize for using the word “density” or “dense” three times in one sentence, but this is a blog, and you should expect subpar prose.) The upshot is that, at least from an environmental standpoint, what matters most is a sort of functional urbanism that allows a high level of non-car travel, rather than simply a high people-per-square-mile statistic. Not really addressed: social and economic justice. Worth reading nonetheless.

This paper from the Victoria Transport Policy Institute does take on the economic side of things, and purports to show that functional urbanism is, in fact, the best policy to promote transportation affordability. Not shocking. What I’m not sure if it covers–I haven’t read the whole thing yet–is how functional urbanism affects economic segregation, which is more of my interest. Read it here.