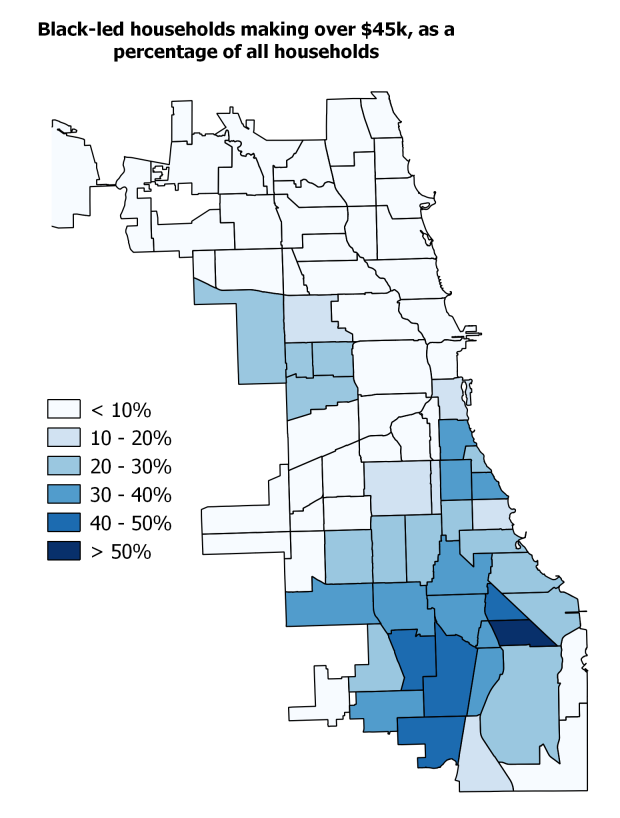

Last week, my post on where Chicago’s black middle class lives was republished at Crain’s. From there, it received many responses making many different points, which I might take on in a separate post at some point. But for the moment I wanted to highlight two recent comments left at the original piece.

DanaC:

My friends and I are all college educated, (many with MAs) Black twenty something’s who are looking to establish roots soon. Most of us have any desire to move to Chicago from the burbs (South Holland, Olympia Fields etc). Personally, despite the great amenities the North side has to offer, I am very apprehensive about living there because of higher rent and racial tensions (and frankly ,in my experience, north siders just aren’t as friendly). However, living on a more friendly (and adorable) south side means no grocery stores, no shopping, no restaurants, no nightlife, no fun. The south burbs aren’t as bad but are still generally lacking in amenities. Here’s an experiment, on google maps, look up your favorite places (Target, Starbucks, Thai food restaurants etc) you’ll find next to none on the south side. So what many (and I mean MANY) of us would prefer is to move out of state all together. That sounds extreme, but I literally feel that I have nowhere to live in Chicago.

Naomi Davis:

I imagine some rationale for lower household incomes for African Americans living north is that a significant percentage could be early career professionals, living single, making modest incomes relative to established families and professionals in their areas. I lived the majority of my years in Chicago as one such professional, only moving to the south side to combat cultural isolation and to pursue my life’s work in a social milieu I assumed would be more supportive to dating, marriage, community-building. People of color in the neighborhoods where I lived/loved for decades – Lincoln Park, Old Town, Uptown, Edgewater, Rogers Park, Bucktown – were either just like me or low-wage immigrants or low-income families, arguably remnants of pre-gentrification, but not necessarily the “public housing/SRO” enclaves referenced in previous entries. I also appreciate this more nuanced conversation around race and household income, core to my work. I bristle at the notion that a prime way to improve life in African American neighborhoods is to import whites – a surprisingly common thought. While my org actively invites blacks with higher incomes to “move back home” to our hard-won legacy communities, I’m always surprised that few consider the complementary alternative of helping lower-wage families increase their household income – again, core to my work. Complicated, of course, by seemingly implacable structures holding poverty in place. Implacable perhaps, but not impossible to transform. Gets me out of bed in the morning, anyway. Many thanks for your thoughts. I look forward to hearing more.