(As a foreword: I’m very conscious, as I write this, that I’m explaining something a large number of readers already know; I want to acknowledge that what I’m doing is not unearthing some previously-undiscovered secret, but trying to demonstrate a few of the basic facts of the city’s social geography that really, truly are mysteries to a huge number of people, both in Chicago and in the rest of the country. It would be nice if we lived in a world in which the black middle class were not an exotic demographic to most non-black Chicagoans, let alone the dominant view from outside the city: but we don’t, so here we are.)

There are at least three ways one might go about answering that question.

1. If you picked a random middle-class black person, where are they most likely to live?

To answer this question, you probably just want to count up all the middle class black households and tally them by neighborhood. So that’s what I did. The tricky part, obviously, is defining “middle class.” In the end, I went with something like what I did with my Chicago income segregation maps: households making at least 75% of the metropolitan average income, which works out to about $45,000 a year. There are a million problems with this: it doesn’t account for household size, or life station (a 26-year-old with a bachelor’s making $40,000 doesn’t count, even though nearly anyone who met them would consider them middle class, while a single parent with four children making $45,000, whose economic and social position is likely much, much more precarious, does), or any number of other things. I considered using education, but in a city like Chicago – and this is especially true among African Americans, I think – a huge number of people with middle-class lives have union jobs that don’t require a college education.

Anyway, with all those caveats, here’s the map:

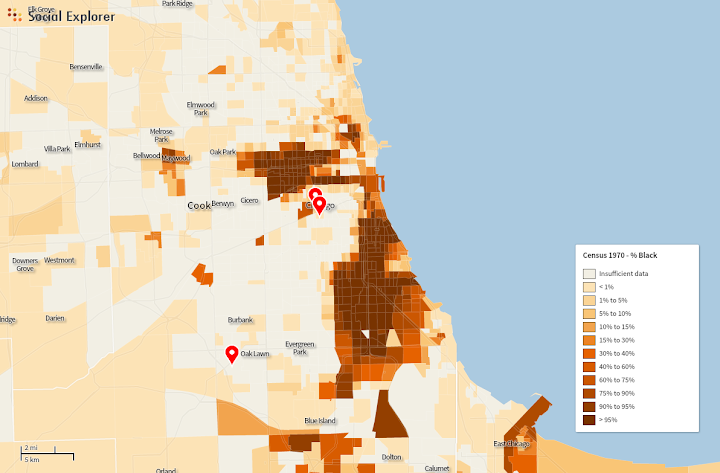

So the answer is mostly on the South and West Sides: that’s Austin there on the far West Side, with the largest number; Roseland, Auburn Gresham, and South Shore are the leaders on the South Side.

So the answer is mostly on the South and West Sides: that’s Austin there on the far West Side, with the largest number; Roseland, Auburn Gresham, and South Shore are the leaders on the South Side.

There are things to say about this, but I’m going to go through the next two maps before I say them.

2. If you picked a random person in a given neighborhood, what’s the likelihood that person would be black and middle-class?

In effect, what this does is control for the number of people in each community area. Austin, for example, which looked super impressive in the first map, now looks less impressive; it turns out that it has a lot of middle-class black people mostly because it has a lot of people, period.

Anyway, the standouts now are Calumet Heights, the darkest-blue trapezoidal shape on the far Southeast Side; Avalon Park just to the north; and Roseland, Washington Heights, and West Pullman on the far, far South Side.

3. Finally, if you picked a random black householder in a given neighborhood, what is the likelihood that person would be middle-class?

This is a considerably weirder, and in some ways more misleading, map. There are now standouts on the Northwest and Southwest sides, in addition to the far South Side; but, if we refer back to the first map, we see that most of those places have vanishingly few black households to begin with. In fact, it’s much worse (in the sense of the numbers are much smaller) than that map even suggests: in many of the darkest-blue areas, we’re talking about dozens of households. Many of these are areas that, up until twenty years ago or so, had literally – or almost literally – zero black residents. To the small extent that they’ve been integrated since then, they’ve been integrated with solidly middle-class people.

Anyway, a few notes on the whole thing:

1. The black middle class exists in Chicago. In large numbers. This shouldn’t really be news, but speaking in my capacity as a white person who knows a lot of white people, and other people of various ethnic backgrounds from the North Side and suburbs and other parts of the country/world, it really is.

2. Perhaps even more importantly, the vast majority of Chicagoans who are both black and middle-class live on the South Side, and to a lesser extent, the West Side.

3. The concentration of middle-class households varies dramatically from one black neighborhood to another.

4. Still, the majority of Chicagoans who are middle-class and black live in neighborhoods that are mostly not middle-class – as opposed to Chicagoans who are middle-class and white, for whom the opposite is true. In this way, Chicago is pretty similar to the rest of the country.

The takeaway, for me, is that these maps contradict two of the biggest lies – or, if we’re being kind, misconceptions – about the social geography of Chicago. The first is that the black neighborhoods of the South and West Sides are an undifferentiated landscape of economic hardship. This is false in a couple of ways. For one, though there are, in fact, many people who are suffering for want of a decent wage in these areas, there are also many thousands of households that are not. (Though they are likely still disadvantaged by other consequences of segregation, including worse access to jobs and basic amenities, higher crime, lower-performing schools, etc.)

For two, just like white, Hispanic, and Asian people, black people are segregated by income. That is to say: some black neighborhoods are much wealthier than others. Of course, this kind of stratification is complicated, since it’s layered on top of – and interacts with – racial segregation. But the view of Chicago as bifurcated between the privileged North Side and deprived South Side needs to get sophisticated enough to recognize the major differences in privilege/deprivation between, say, Englewood and Calumet Heights. It also needs to recognize that even in neighborhoods that are majority low-income, there are generally a significant number of middle-class residents.

The second big lie, related to the first, is that basically everyone on the South and West Sides would get out if they could. This is sometimes stated explicitly; more often, I think, it’s the unspoken assumption that frames most outsiders’ conversations about those parts of the city. It assumes that everyone in Chicago follows roughly the same ladder of neighborhood prestige: one that tops out in Wicker Park, or Lincoln Park, or North Center, or Norwood Park, depending on your family status and subcultural preferences.

But this isn’t remotely the case. Someone who had only lived on the North Side – or outside the city – might figure that the reason there are so few black people (or Latinos! more on that in a sec) in, say, Lakeview, is that Lakeview is so expensive, black and Latino people have lower average incomes, etc., etc. And surely that is, in fact, a large part of the answer. But it’s not the entire answer, and one way to prove it is to show that, actually, the median black householder in Lakeview actually makes less money than the median black householder in Roseland, a neighborhood whose name is usually accompanied in media reports with adjectives like “struggling,” or “blighted,” and so on. It’s actually not even close: over $40,000 in Roseland, versus $33,000 in Lakeview. Those sorts of inversions of North Side/non-Chicagoan perceptions about neighborhood prestige are actually pretty common: black median household income is $24,000 in West Town, $31,000 in Lincoln Park, and $35,000 in North Center, but $39,000 in West Pullman, $42,000 in Washington Heights, and $56,000 in Calumet Heights. And in Ashburn – a neighborhood on the very southwestern edge of the city that’s about 50% black, and which most North Siders (including me, until friends moved there a few years ago) have never even heard of – it’s over $70,000.

Why does all of this matter? Number one, it’s something that lots of people are wrong about, and I don’t like it when people are wrong about things. More generally, though, widely-held perceptions of neighborhood quality and prestige – especially when those perceptions are held by people with lots of economic and political power – play a huge role in shaping the future of any given neighborhood. From a governance perspective, there are lots of reasons you’d want the people in charge of a city to have an accurate impression of the communities they’re governing before they start making up policies for them; but also from a purely social point of view, the fact that most non-black Chicagoans – and the vast majority of non-Chicagoans – can’t distinguish between Englewood and Calumet Heights means that they won’t ever visit, spend money, and certainly won’t consider living, in neighborhoods that they would likely find generally pleasant. (I apologize for picking on Englewood: I definitely don’t mean to suggest that it doesn’t also have positive qualities, or that no one should go there. I’m making some big-picture observations about the size of its challenges relative to other neighborhoods, and common ways that people react to places with those kinds of challenges.) In short, it’s hard to build much of a local economy in a place that 75% of the population shuns without even thinking about it. (Read Robert Sampson’s Great American City for more on that.)

Anyway, this post is now long enough: I have more to say, but I will put it off to another time. I’ll leave you with two final maps: versions of map #1 above for Latinos, whites, and Asians. They’re fairly self-explanatory, but suffice it to say that most of this post could be rewritten, with only minor edits, to apply to Chicago’s Latino middle class as well.