I looked at my last post again and realized that, as written, it is entirely race-neutral. Is race beside the point of municipal-level policies that affect inequality? Obviously not. And yet.

And yet I have become aware, in the course of thinking about these things, that when I use the words “integration” and “segregation” in a contemporary urban context I mean, by default, integration and segregation by economic class, and not by race, which is obviously the default for most people. That is, when we want to talk about class-based segregation, we have to say “class-based” or “income-based.” We don’t have to say “race-based”; it’s implied. The opposite is now true for me, or at least the monologues in my head. My language has revealed that I believe class segregation is the more fundamental problem.

Why is that? And is it fair?

This, I suppose, is my thinking: There is something necessarily wrong with economically-segregated neighborhoods that is not necessarily wrong with racially-segregated ones. I can think of two things, in fact. Number one is that in any very roughly capitalist, modern society, it is hard to imagine a disproportionately low-income neighborhood that does not suffer the kinds of neighborhood effects on education, health, mobility, etc., that I mentioned in the last post. It just seems impossible. Number two is that economic class has not traditionally – at least not in the United States – been a dominant cross-generational cultural marker in the way that race or ethnicity has been. That is to say that being of a particular race puts you in a more defined community than being in a particular economic class, and so there seems to be more of a positive reason to have some amount of physical clustering along those lines.

(I don’t think I can emphasize enough, of course, that I AM NOT endorsing the segregation-exists-because-people-want-to-live-among-their-own-kind hypothesis, which is falsified by every possible empirical and non-empirical and imaginary investigation, from actually asking people what kind of neighborhoods they would like to live in, to a historical examination of how neighborhoods actually came to be segregated, and so on. But even in the absence of all of this, I am saying, there would be some push for some moderate amount of clustering, in the same way that, for example, being a young person puts you in a community that creates a push for clustering and the creation of neighborhoods that are somewhat disproportionately full of young people. These neighborhoods are not 98% young people, or anywhere near it, as so many American neighborhoods are 98% black. To get to 98% anything, or anywhere near it, you pretty much always need massive coercion.)

I would add that the purely race-based barriers to racial integration are less today, I think, than the purely income-based barriers to economic integration. Race-based barriers are very alarmingly high, of course. There is steering and lying and mortgage discrimination and so on. But if you are a black middle-income couple and you are committed to moving to a majority-white neighborhood, you will probably be able to do so, even if it takes longer and is more costly (and puts you in a less-affluent white neighborhood) than if you were not black.

Low-income people, on the other hand, also face a variety of discriminatory practices, but the most important one is simply the price of real estate, which makes discriminatory practices moot in many, if not most, instances. If you cannot pay the going rent for a given neighborhood or suburb, you don’t even have a theoretical recourse. Except Section 8, I suppose, if your income is low enough, which puts you back in the world of discriminatory practices – one in which it’s perfectly legal in most places for landlords to flatly state that you are not welcome. The fact that racial segregation is slooowly declining, while economic segregation is skyrocketing, is more evidence of this.

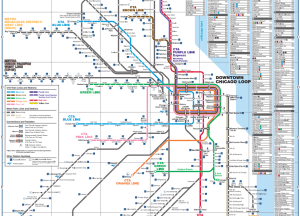

But. There are at least two very obvious problems with my argument. The first is that because race is still a characteristic that on its own provides privilege or the lack of it, there is something inherently wrong with racially segregated neighborhoods in the United States in 2013, and, in fact, there will be for the foreseeable future. The fact that it’s possible to imagine a world in which that is not the case doesn’t mean a ton. The existence of a massive number of communities in Chicago, and across the country, that are 95%+ non-white is itself evidence (if more evidence is necessary) that race continues to provoke coercion.

The other thing is that, largely because of point #1, race and class are so intermixed that it’s not really practical to talk about integration of what without integration of the other. Especially if we take into account wealth, and not just income, economic status is so skewed by race that serious integration along one of those axes would necessarily create integration along the other.

So I have built up an argument in favor of focusing on economic segregation instead of racial segregation, and then knocked it down. I think the wrongness – in both the ethical and the logical sense – of privileging the economic issue to the exclusion of the racial one is clear.

There is one last factor, though, which is practicality. From a policy perspective, at least, economic segregation looks much easier to deal with (in most instances). The issue is, on the one hand, about just giving lower-income people more money so they can pay rent; and, on the other, allowing developers to increase housing supply so prices go down. There are huge logistical and political obstacles to that, of course, but the basic ideas are there, and there’s a fairly diverse and vocal constituency for them, from the large number of people who would like to pay less for housing – or be able to afford better housing given their budget – to the ecosystem of affordable housing nonprofits and CDCs, to the developers who would like, selfishly, to make money from building more stuff.

On the other side, it’s not at all obvious how you significantly speed up racial integration. Increased enforcement of anti-discrimination laws would help, of course, but almost by definition it’s difficult to prove those cases without a huge amount of time, energy, and money. Real estate counseling programs help, but not that much, and plus it’s kind of paternalistic, which may or may not bother you. Moreover, there just isn’t any massive, organized groundswell in favor of racial integration. Steve Bogira has been doing a Ben–Joravsky–on–TIFs thing with racial segregation, which is terribly important, and he is one of the only people, if not the only person, with real media access who’s doing that in Chicago. But his own articles are often about the fact that it’s basically impossible to get anyone with power to even acknowledge that government might have some role to play in directly promoting racial integration.

I guess what I’m saying is that this, in the end, is why I spend more energy thinking about policy responses to economic segregation than policy responses to racial segregation, and probably will continue to do so: it seems less hopeless. That, and, like I said before, promoting economic integration will almost certainly push along racial integration as well. But I don’t think coming to that conclusion is an excuse for ignoring the very real relevance of race, and I think it’s important that in particular the wonkish conversations a la Glaeser and Krugman and Yglesias and Avent (all white, like me! a hint of more of the problem) don’t become so focused on pure economics that they forget that.