Chicago is a city obsessed with neighborhoods, neighborhood boundaries, and neighborhood character, and therefore with neighborhood change. Demographic trends, from the rapidly declining black populations on the South and West Sides to the gentrification of the Northwest Side, get a lot of play in the media and in conversation. Which is why it’s weird that we’re in the middle of a demographic transition that is already of historic importance for the city and almost no one is talking about it.

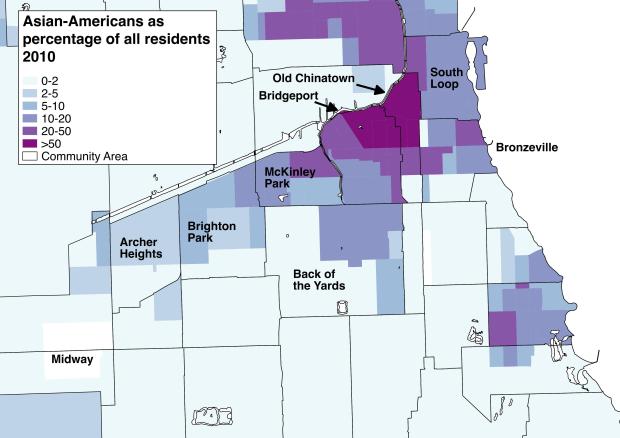

Which is: the Southwest Side, first a bastion of European immigrants and their descendants, and then of Mexican immigrants and their descendants, is now gradually filling with Chinese immigrants and their descendants.

In 1990, there was virtually no presence of Asian-Americans east of the Dan Ryan into the South Loop or Bronzeville, or south of Pershing (39th St.), except for Hyde Park. (I’m going to say “Asian-American” here, because those are the Census numbers I have, though it appears that nearly all of the Asian-Americans in this part of the city are of Chinese descent.) There was no significant (over 10% of residents) presence east of Racine (1200 W) or so, or south of 31st St. By 2010, there was a continuous band of Asian-American population down Archer Avenue, the backbone of the Southwest Side, nearly all the way to Midway*, as far south as 51st St. and as far west as Cicero (4800 W). There were continuous pockets of neighborhoods over 10% Asian-American stretching from the lake to California Ave., more than four miles away—and a nearly continuous stretch from the lake to Damen, more than three miles away, that were over 20%.

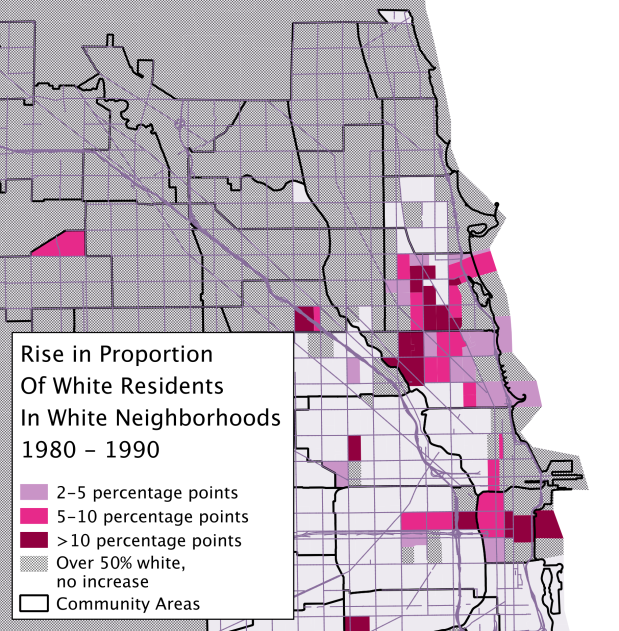

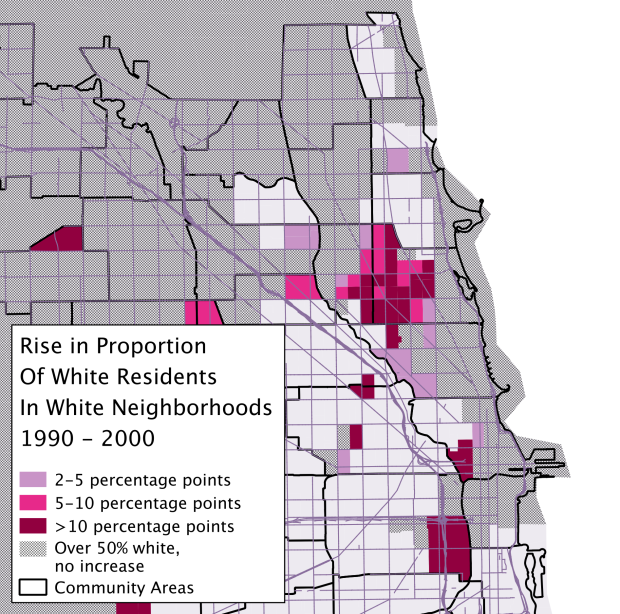

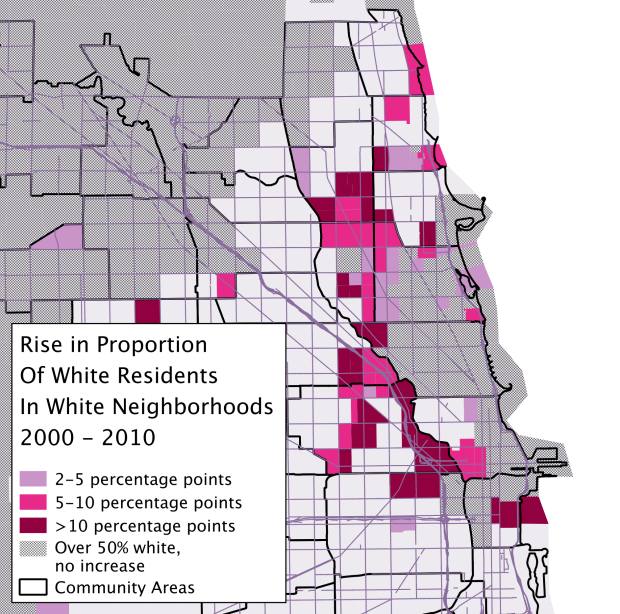

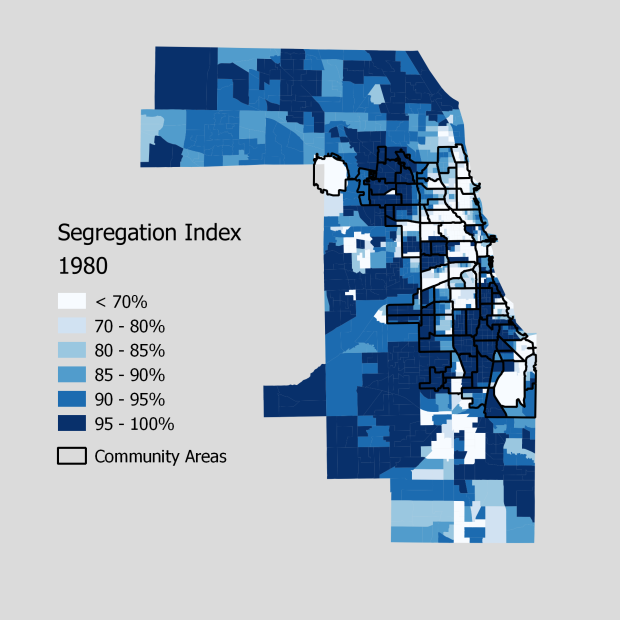

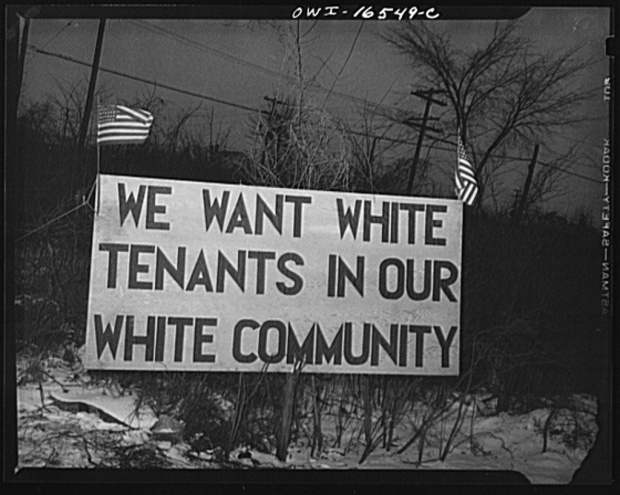

Now, to be fair, this alone isn’t especially dramatic in the context of Chicago neighborhood change. Certainly in the white flight era, a neighborhood’s racial makeup could transition much more quickly, and the gentrifying parts of Logan Square, say, may appear more unrecognizable to a decades-long resident than sections of Brighton Park that have gone from zero to eight percent Chinese-American in twenty years.

But there are several reasons, I think, that this movement is really notable.

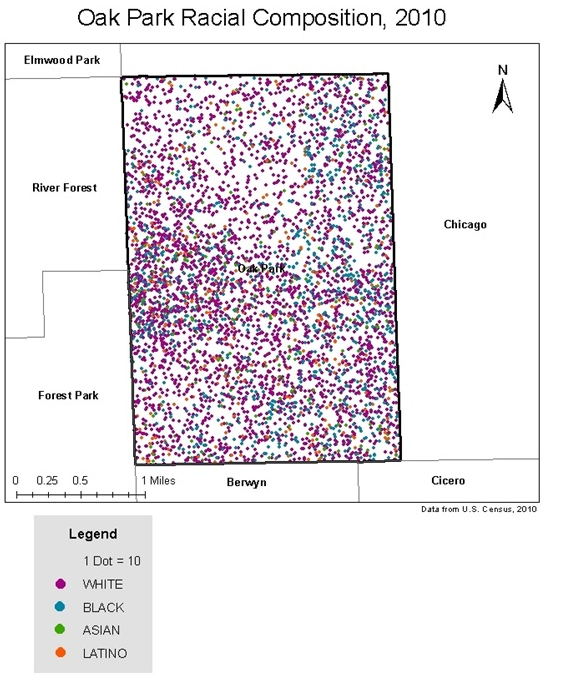

First, Chicago has for many years been seen by many as culturally and politically divided into three major ethnic groups: Black, Hispanic, and White. In fact, the city was notable for how evenly divided the population was between those three groups, and for the extent to which their segregation allowed distinct racially-specific geographic political representation. But though Asian-Americans have been in Chicago for a long time—in 2012, Chinatown celebrated its 100th year—they are only now beginning to reach a point where the population is large enough, and geographically concentrated enough, to demand that kind of local political representation.

Already in the 2010 district remapping, neighborhood organizations were able to lobby—unsuccessfully—for a ward around Chinatown that would have been over 40% Asian-American. And in the March primary elections, one of the people asking for that remap, Theresa Mah, beat out a Hispanic candidate for the Democratic nomination for a state legislative seat. By the 2020 remap, it seems very hard to imagine that there will not be an Asian-American majority, or strong plurality, seat on the City Council, bringing a kind of ethnic representation to City Hall that that community has up to this point lacked.

Second, the growing Asian-American presence on the Southwest Side offers the city a glimmer of hope to a demographic problem that it seems to not yet realize it has: the dramatic national decline of Mexican immigration. That was a key factor in Chicago’s poor showing in recent Census population estimates, as Latin American immigration had essentially been keeping Chicago demographically afloat since at least the 1990s.

The major beneficiary of that influx was the Southwest Side, where predominantly Mexican-American families rejuvenated neighborhoods whose White ethnic occupants were either aging out or moving out to the suburbs. But now it appears that Mexican-Americans are following the Lithuanian-Americans down Archer Ave. past the city limits, and without new arrivals, it’s unclear what will happen to the gateway neighborhoods. Between 2000 and 2010, Pilsen lost a quarter of its Latino population, or 10,000 people—far more than the 850 Whites it gained, and so probably not mainly explained by gentrification. Little Village, which was certainly far from the gentrification frontier in 2010, lost 10,000 Latinos as well. As the 850 number suggests, gentrification isn’t likely to spread too far down Archer Avenue in the near future. Rather, Chinese-Americans appear to be the most likely candidate for keeping the Southwest Side demographically healthy.

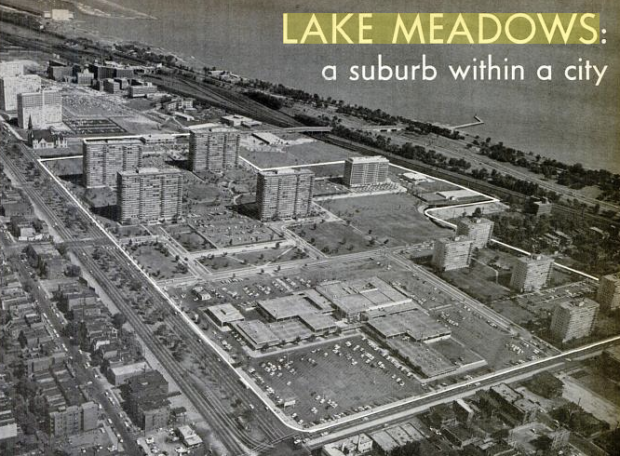

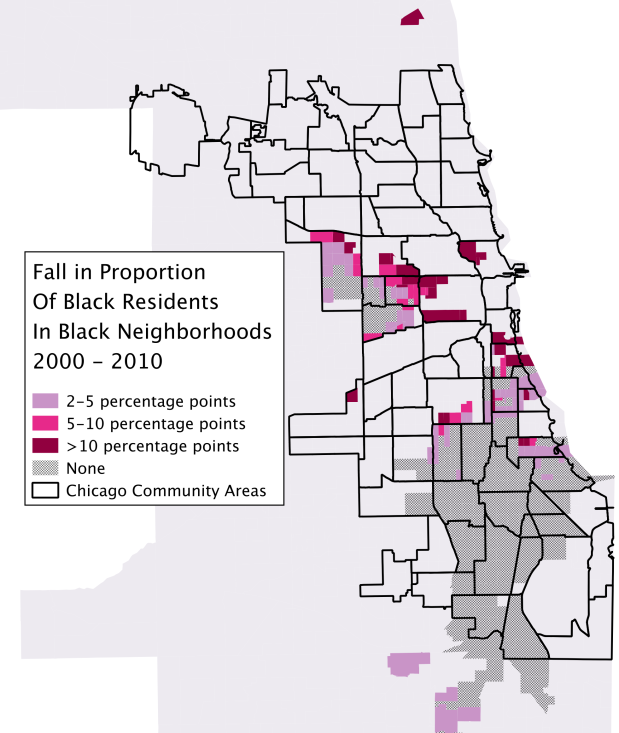

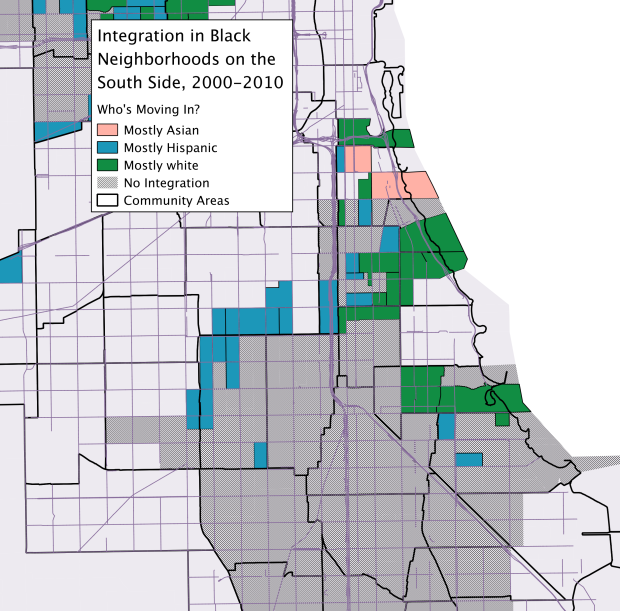

Third, Asian-American residents haven’t just spread west from Chinatown; they’ve also spread east, to Bronzeville. While I’ve written about how one of Chicago’s longstanding (and, of course, deeply and transparently racist) rules of neighborhood change—non-Blacks never move in significant numbers to Black-majority neighborhoods—is being threatened by Hispanics, Whites, and Asian-Americans in spots all over the city, nowhere has a Black-to-another-ethnic-group transition gone farther than northern Bronzeville. The area bounded by the Stevenson, the lake, King Drive and 31st St. was 73% Black in 1980, and just 55% Black (and 36% Asian-American) by 2010. The Census tract just to the west has gone from 96% to 73% Black, and 1% to 13% Asian-American, over the same period; just to the south, in the Lake Meadows area, the numbers are 92% to 75%, and less than 1% to over 18%.

Again, these are a far cry from the total demographic overhaul that we’re used to seeing in some areas—but nevertheless, it puts the city in completely uncharted territory. As far as I can tell, this is the first real racial desegregation of a Black neighborhood in the history of Chicago that did not involve the wholesale government-led demolition of Black housing, a la Cabrini-Green. And the implications for Bronzeville go beyond the Chinese-American community, since creating a substantial non-Black presence may open the doors to people of other ethnic backgrounds as well, especially in an area adjacent to the rapidly gentrifying South Loop.

Finally, there’s a sort of meta-point to be made here, which is that it’s very odd that all of this has flown so far under the radar. When I brought this up on Twitter, I suggested it was because most media outlets only really care about neighborhood change when white people are involved, either as colonizers (gentrification) or evacuators (white flight). A transition from one group of people of color to another group of people of color just doesn’t rank. Someone else suggested that it might simply be the invisibility of Asian-Americans in broader media in general. Another possibility is geographic, given the well-established lack of interest in non-homicidal events south of Cermak or so on the part of a lot of Chicago media.

I’m not sure what else to say about that, except that none of these are good, and all suggest some amount of course correction is needed (and I don’t exempt myself from that). I’d love to see some reporting on what these transitions look like from the ground—and if I’ve somehow missed reporting that has been done, someone please let me know!

* If it seems that I’m making a big deal out of a few percentage points in some areas, I would just point out that historically, Chicago-area segregation has led to situations in which many neighborhoods would have virtually no representation from one or more ethnic groups; that was certainly the case with Asian-Americans on most of the Southwest Side. Breaking that barrier from “none” to “a few”—especially when, nearby, those numbers grow more substantially, suggesting a broader trend—is a notable step.