The answer is: sort of for traditional public schools; definitely not for charters.

This post began when I read reports from WBEZ and Catalyst Chicago about the rapidly growing number of public high schools in the city:

But Chicago high school students are being spread thinner and thinner across all those choices. High school enrollment has grown slightly in the last decade, around 8 percent. But the actual number of high schools has exploded in that time, from 106 to 154 today. Nearly all the new schools are charters.

Roberto Clemente Community Academy in Humboldt Park is one of [the schools facing declining enrollment]. It’s an eight-story building. Until recently escalators carried 1,800 kids from floor to floor. There are just 130 freshmen enrolled today. Another 473 freshmen live in the area but go to high school somewhere else. In fact, the Noble Street network of charter schools, with its various campuses, enrolls more students from Clemente’s attendance area than Clemente.

This is certainly not the kind of problem most people think about when they think about CPS – who would have guessed that, in an era of massive school closings, Chicago has increased the total number of high schools by 50% in a decade? – but it’s a big one. Underenrolled schools like Clemente have to cut extracurricular programs and special academic classes that no longer have enough students to support them; they also end up requiring extra financial help from the district just to maintain a functioning building.

If you wanted to put a positive spin on this, of course, you might say that Chicago has created a functioning market in high schools: students and their families are free to choose the ones that offer a better education, and if that creates winners and losers, good! The bad schools ought to fail. That’s exactly what charter proponents have been asking for all along.

But that only works if students are leaving bad schools and enrolling in good ones. If we’ve just created enrollment churn without moving students from bad to good, all we’ve managed to do is add another serious problem to a district that already had plenty.

So which is it?

Happily, CPS provides data on 1) enrollment in every school in the district and 2) every school’s ACT score. (Here is the obligatory caveat about how good ACT scores do not equal a “good” education. Given the district’s laserlike focus on test scores, though, it seems fair to judge them – on an at-least-you-have-to-be-good-at-this basis – by whether they’re moving this particular needle at all.)

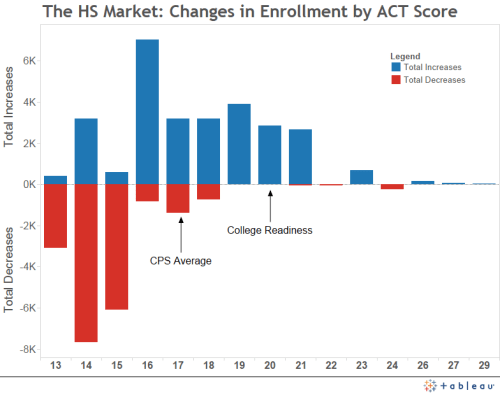

So, using the district’s numbers, I calculated how much enrollment has changed in every high school between the 2005-06 school year and the 2012-13 school year. Then I grouped all the schools by their ACT scores – all the schools that scored 15 in one bucket, 16 in another bucket, and so on – and added up the positive and negative enrollment changes for each bucket. Here’s the graph:

What we should see, if the market is working, is big red bars on the left side, indicating that lots of students are leaving low-scoring schools, and big blue bars on the right side, indicating that people are flocking to high-scoring schools. Obviously, that’s not quite what’s happening. True, it looks like schools with above-average ACT scores are mostly gaining students; and lots of students at below-average schools are leaving. But a lot of those students are going to other below-average schools. That’s why you see sizeable blue bars even way to the left side of the graph. Why, if the market is working, are we seeing any enrollment increases at schools with average ACT scores of 13 or 14, both of which are truly, truly abysmal? Random guessing, for comparison’s sake, gets you a score of 12. Twenty is considered the minimum to get into college.

Just to be clear about what these graphs show: It is not only that some students are enrolling at bad schools. People move, and new classes come in, and so on, and so it would be highly surprising if any school was so bad that not a single new student showed up. What these numbers show is that some terrible schools are seeing their total enrollments increase, to the tune of about four thousand students in all at schools with an average ACT score of 15 or lower.

So the fact that enrollment decreases outnumbered enrollment increases helps only a little, because it doesn’t change the fact that some of the “winners” in this market are providing some of the worst educations in the district. That suggests a problem.

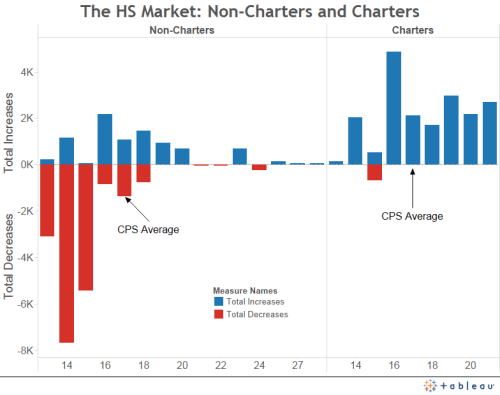

Part of the problem is explained by breaking out that graph into charter schools and non-charter schools:

Now things are a little bit clearer. There are still some enrollment increases at non-charter high schools with very, very bad ACT scores, which is still a problem. But they’re a much smaller proportion of all student migration, and are much more massively outweighed by enrollment decreases at other low-scoring non-charter high schools.

But oh man, look at those charter numbers. The high-scoring charters have enrollment increases. The mediocre-scoring charters have enrollment increases. The low-scoring charters have enrollment increases. The very-low-scoring charters have enrollment increases. Basically all charter schools have enrollment increases, no matter the quality of their education.

Why might that be? I can think of two general possibilities:

- Charter schools provide a better education than non-charters in ways that don’t show up on ACT scores. For example, a zero-tolerance approach to discipline that creates a safer learning environment. Or a curriculum that encourages more creative and critical thinking skills. Or teachers and administrators who forge tighter, more nurturing relationships with students and parents.

- Charter schools get better PR than non-charters, and so parents want to enroll their children there whether or not they actually provide a better education.

Obviously Possibility 1 would be much much better news for the market in high schools than Possibility 2, which suggests a major kind of failure. My guess is that both are going on, though I don’t feel like I have any particular insight about in what proportion.

That said, I’m going to go ahead and suggest that there is almost no way that the unmeasured benefits of Possibility 1 actually outweigh the awfulness of any high school where the average ACT score is 13 or 14. I am definitely in the camp that believes we make too much of standardized tests in education; and yet, having been (very briefly) a teacher myself, I know that there are scores below which there is just no way that a student has received a decent education; scores low enough they pretty much guarantee a failure of adult literacy and numeracy that not only rules out any kind of higher education, but even the most menial of non-physical work, as well as physical work that requires any kind of computation or written communication. In other words, these schools are graduating people who simply have not been prepared to participate as adults in our society, and we’re rewarding them by handing them responsibility for thousands of extra students.

* * *

But let’s pull back a little bit. In the beginning of this post, I asked: Is Chicago’s market in high schools working? Are students moving from bad schools to good ones?

The numbers have established, I think, that on one end of the spectrum – low-performing charter schools – the market is failing spectacularly.

But it’s clear from the first graph that, overall, there is some movement to the right – that is, to higher-scoring schools. Specifically, the median net enrollment decline has been from a school with an ACT score of 14.9, and the median net enrollment increase has been to a school with an ACT score of 17.7. That’s a huge and heartening gap.

Unfortunately, it also indicates one of the major problems with the “school market” approach. Why? Mostly because, as I mentioned earlier, the minimum ACT score that indicates college readiness is a 20. Very few of the schools winning more students in this market graduate a large minority – let alone a majority – of seniors who score that high.

But not just that. CPS’ districtwide average score is a 17.6. Meaning that half of all enrollment increases have been at schools that are below average, even by CPS’ low standards.

Why would that be? I don’t know, but I can take a couple of guesses. For one, the top-scoring high schools in the city are mostly selective enrollment, and unlike neighborhood schools – which have to find room for students in their attendance areas no matter what – they won’t grow significantly unless they get extra room. Or maybe, since parents often send their children to schools where they know other families, there’s something going on with social networks.

More importantly, I would imagine, is that there is a geographical problem: most of the city’s very bad high schools are in certain neighborhoods on the South and West Sides, and a disproportionate number of the above-average ones are on the North Side. One-way commutes of over an hour would definitely be a disincentive to send your kid to the better high school across town – especially if you live in an area where getting to and from the nearest public transportation means crossing gang lines.

This isn’t a definitive map – it only shows neighborhood schools, excluding charters, etc., but it gives a general sense of where the high-scoring and low-scoring high schools are around the city, and how tightly the low-scoring (Level 3) schools cluster, and how far you might have to travel from one of the low-scoring clusters to something better.

* * *

So Chicago has a market in high schools. CPS created this market in large part by increasing the total number of schools by 50% over about ten years. The market is creating clear winners and losers. For the losing schools, the market is actually a disaster. Whether this is worth it for the city overall is to some extent a judgment call, but to me it seems pretty doubtful. Even though there is some movement to higher-scoring schools…

- …half the city’s enrollment increases are happening at schools with ACT scores that are below district average.

- …charter schools, which make up virtually all of the schools added to the district over the last decade, appear to be almost totally unaffected by whether or not they provide a good education to their students; they grow rapidly regardless.

- …there are major structural impediments to moving kids from low-scoring to high-scoring schools.