And that matters because the people who make decisions about transit investments – politicians – look at how many of their constituents benefit from a given service as a major component of whether they benefit politically from supporting it.

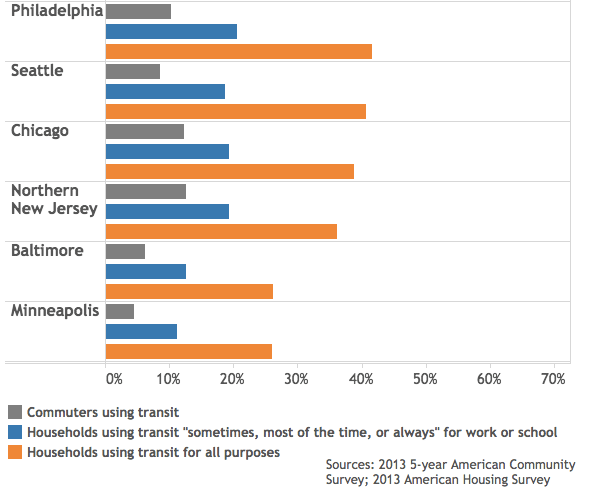

And if they’re just looking at commute share, they’re looking at too few people. Even transit-rich metropolitan Boston doesn’t look so great by that metric: only 12% of workers there usually take transit to their jobs. But 29% of households include someone who regularly takes transit to school or work, and fully 56% of households use transit for at least some of their trips. In sprawling Houston, just 2% of workers commute with transit – but more than twice that proportion of households use transit for work or school, and more than one in ten households use transit for some of their trips. That’s still not great, but it’s much more significant than the minuscule commute numbers. It also suggests that even in one of the most transit-hostile regions of the country, a remarkable number of people find public transit useful for certain trips, forming a toehold for better service to produce even more ridership.

Monthly Archives: May 2015

Why are there no “pedestrian streets” in black neighborhoods?

It’s a bit weird that Chicago has something called a “pedestrian street designation” – after all, people walk on pretty much literally every single street in the city. But it does! Official “pedestrian streets,” which have existed since 2004, are designed to “promote transit, economic vitality and pedestrian safety and comfort” by disallowing certain things, like parking lots facing the sidewalk, and encouraging others, like storefronts and sidewalk cafes. The city’s transit-oriented development ordinance also applies up to two blocks from an L station along pedestrian-designated streets, as opposed to one block on other streets.

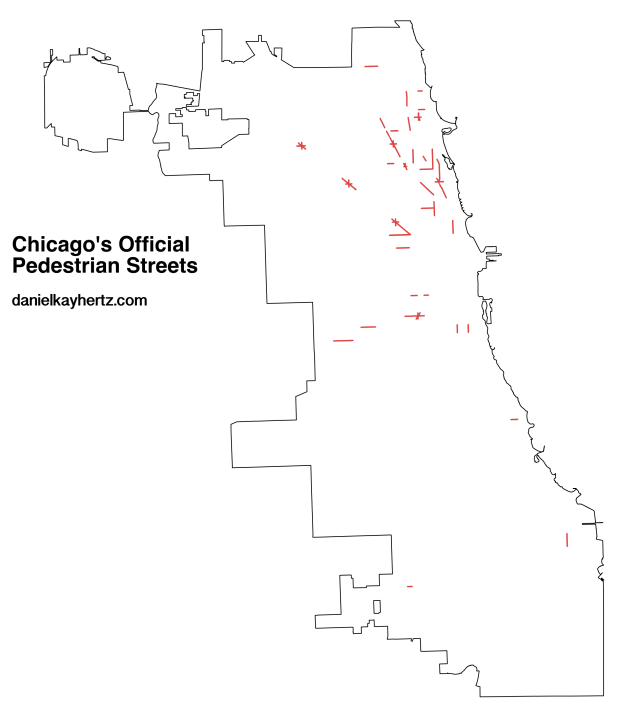

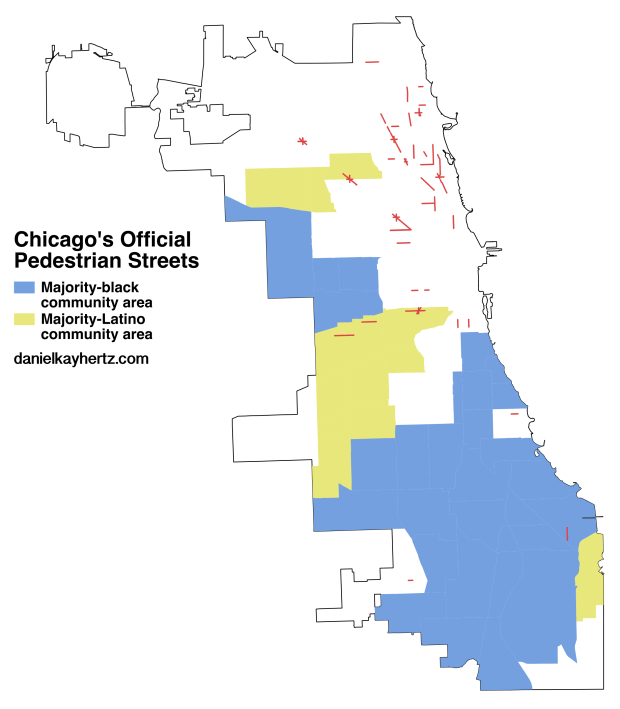

Recently, I saw a map of the city’s pedestrian-designated streets for the first time. This is what it looked like:

This is a map that made me say “hmm.” If you have any sense of Chicago’s racial and economic geography, it is probably making you say “hmm,” too. But just to hit the point home:

There is literally one pedestrian street in a majority-black community area: Commercial Avenue in South Chicago, between 88th and 92nd Streets. By contrast, the North Side east of the river is absolutely lousy with them; Milwaukee Ave., the retail backbone of the Northwest Side, has several large districts radiating from six-way intersections; and the Latino section of the Southwest Side, though it has way less than the North Side, at least has pedestrian designations on the busiest portions of 18th, Cermak, and 26th Streets.

To be clear, the people in charge of assigning pedestrian street designations are aldermen, not CDOT. That is, the issue isn’t that the Mayor’s Office is just choosing to give North Side streets “pedestrian” status and not South Side streets. But still, it’s a pretty notable pattern.

How much does this matter? I don’t know. You could observe, of course, that people in Lincoln Park, Lakeview, Uptown, West Town, and their aldermen, appear to believe that pedestrian street designations matter enough to slap them all over their neighborhoods. Alderman Ameya Pawar, for example, has been quite vocal in his belief that making commercial streets in his ward more pedestrian-friendly will improve his constituents’ quality of life and promote economic development, not to mention reduce injuries from car accidents.

And although people on the South and West Sides may have different concerns and priorities, certainly one of them is economic development and thriving retail districts, which exactly the sort of thing the pedestrian street designation is designed to support. Part of the issue is that a pedestrian street designation – and the somewhat more attractive street that results – is hardly a guarantee of new businesses. Underlying economic factors and the perceptions of business owners matter much more.

But a pedestrian designation is such a low-cost exercise that I’m not sure that explains it. More likely is that there’s a fear that the kind of businesses that have chosen to move into black neighborhoods – disproportionately national chains with auto-oriented cookie-cutter designs – would be deterred by rules that forced them to adopt more pedestrian-friendly formats.

There may be some legitimacy to that. But, for one, there’s more than enough room to place some drive-through restaurants in South Side neighborhoods while preserving and enhancing pedestrian-oriented retail streets. And for two, pedestrian-friendly design is likely best for the long-term economic health of those communities. After all, not only is the property value bonus for walkable neighborhoods well-documented, but there are plenty of South Siders who have noticed that there’s a difference between, say, Clark St. and Cottage Grove – and want to close that gap.

(I’d also note, as an aside, that the way the pedestrian street law is written seems to disadvantage South Side neighborhoods. The ordinance stipulates that pedestrian streets should be designated in places where there are “very few vacant stores,” which excludes many communities with trouble attracting retail – which is to say, most black communities in Chicago. But if the point of the law is to promote economic development, why would you specifically exclude places especially in need of economic development? I don’t think that this clause has actually prevented any given pedestrian street designation – I suspect that, as these things generally work, any alderman who wanted one would get it – but I do think it suggests that the law was designed with the North Side in mind. Which is unfortunate.)

Baltimore’s problems belong to 2015, not 1968

I have a new post at City Observatory:

Look what the riots did to Baltimore! Oh wait no…These were taken before the riots. Oops. @MayorSRB pic.twitter.com/2iTsnVDf6G

— Chels (@BEautifully_C) April 30, 2015

In the wake of violent protests against yet another apparent police killing in Baltimore, variations of this meme spread rapidly in certain corners of social media. Their message went something like this: Pundits and politicians may think Baltimore’s crisis began with the first brick that hit a window at CVS, but we – the people who live there – know the crisis goes back much further, and much deeper.

With this in mind, there’s some irony to the spate of columnists warning that the disturbances in Baltimore mark a return to the “bad old days” of the mid-to-late 1960s, when a series of violent protests in America’s black neighborhoods held the nation riveted. Those riots, too, were treated as a crisis by pundits who had not applied the term to decades of housing discrimination, or illegal violence on the part of police officers and white civilians.

But using violent protests as a point of analytic departure – rather than the underlying crises that provoked them – doesn’t just (unintentionally) reveal one of the similarities between 1968 and 2015. It also misses a lot of the major differences.

Rail transit options in Chicago

I’ve written these roughly in descending order of how much sense they seem to make for the city, but I should say that I think context matters an enormous amount in determining what kind of transit service makes the most sense, and this is meant more as an attempt at an outline of the tradeoffs involved for each option rather than a definitive ranking.

UPDATE: I should also have acknowledged that the cost estimates are verrrry rough; the methodology is at the bottom of the post, but several smart people have commented to quibble one way or the other, particularly with the street-running light rail numbers.

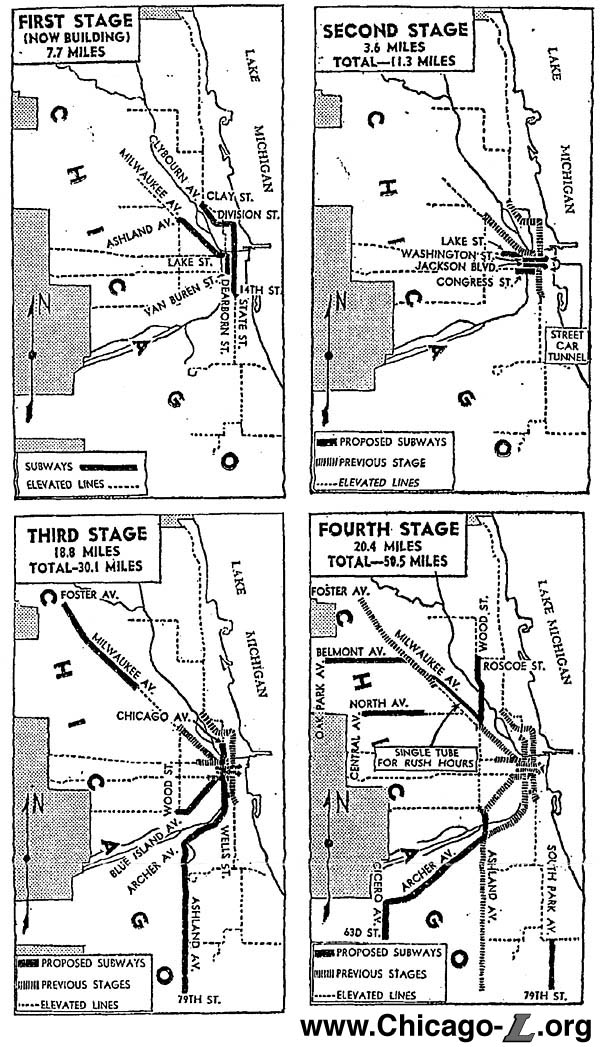

6. Subways

Ballpark Cost: $1.1 billion per mile¹

Sometimes, people say: why don’t we just build a subway? They might say this in reference to the Ashland BRT project, or the Belmont Flyover, or some other place where they’d like a rapid transit line but don’t want to disrupt the flow or aesthetics of the city above ground.

Unfortunately, I have bad news: This is extremely unlikely. It’s unlikely because American subways are just ungodly expensive. (Why are they so expensive? Go ask Alon Levy.) Take, for example, the 16-mile Ashland BRT project. If we held an Ashland subway to the average cost of an American subway, it would run about $17 billion. Even the five-mile first phase would set us back $5.5 billion – nearly 12 times more than we spent to deconstruct and then reconstruct the entire 10-mile length of the Red Line’s Dan Ryan branch in 2013. Chicago’s entire annual budget is only about $8 billion, and the federal government hasn’t been handing out checks for transit infrastructure projects on that scale for quite a long time.

And that’s sort of where the discussion ends. Subways have a lot of benefits – they don’t interrupt, and aren’t interrupted, by surface traffic; they’re protected from the elements; they can move lots and lots of people – but I say that in the spirit of someone window-shopping something very pretty but outrageously unaffordable.

5. Streetcars

Ballpark Cost: $50 million per mile

While subways are potentially useful but logistically impossible, streetcars are logistically simpler but, in most cases, their benefits are much more doubtful.

I should note that I’m using a very particular definition of streetcars here. I have in mind essentially a bus on rails: a relatively short train set designed to travel in the same road lane as cars and other traffic. (Another type of rail transit that some people might call a streetcar, but which I’m calling “street-running light rail,” appears further below.) It looks something like this:

That’s the recently-opened Atlanta streetcar; note the automobiles in the same lane behind it. The problem with this sort of thing, from a Chicago-centric perspective at least, is that it has exactly the same issue that Chicago’s buses have: it gets stuck in traffic, and is therefore extremely slow. Actually, it’s worse than that: buses can move around a stopped cab or double-parked car; a streetcar can’t. In fact, one reporter found the Atlanta streetcar to be slower than walking.

The one advantage streetcars do have over buses is that they can hold more people. But that’s only an advantage if a) you need more capacity and can’t run any more buses, or b) you want to trade higher-capacity vehicles for less frequent service. Since there are virtually no bus lines on which the CTA can’t fit more bus runs – and since I don’t know of any Chicagoans who think that their local bus runs too frequently – those don’t seem super relevant here.

And, for all that, you have to spend $50 million – the cost of one of those super-fancy new L stations – to build each mile before you can even get up and running.

4. Freight right-of-way

Ballpark Cost: $180 million per mile

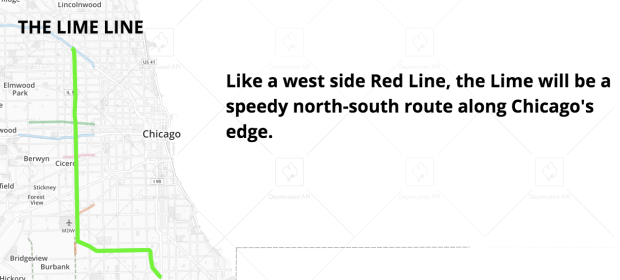

A cheap way to build a rail line that doesn’t have the traffic problems of a streetcar is to put it where there are already train tracks: in a freight right-of-way. That’s mostly what Chicago did with the Orange Line. There have also been proposals to create a line in a freight right-of-way just east of Cicero Avenue – the “Lime Line” in Transit Future.

The problem with this is that most freight corridors don’t go near major residential or commercial nodes. Here, for example, is the area around the Kedzie Avenue Orange Line station:

Unlike L stations on, say, the Green or Brown Lines, you have to walk a quarter mile or more through some pretty uninviting landscapes to get to the places that most people take transit to get to. That problem can be partly mitigated by integrating the station well with frequent buses that take people for their last mile, and the Orange Line makes an effort to do so – but that can still easy add ten or fifteen minutes to a trip, making it much less attractive. That may have something to do with the findings of a study last year that the Orange Line has not catalyzed development in the way that other transit lines have.

3. Elevateds

Ballpark Cost: $250 million per mile

Elevated trains have some of the advantages of subways – they don’t have to even think about street traffic – but are missing lots of others. Namely: they’re exposed to the elements, and are considered by most people a bit of an audiovisual disaster. They’re much, much cheaper – enough so that one could imagine the city actually procuring the money to build one – but politically quite difficult to build in places where lots of people already live and have bought homes on the assumption that there would not be a train rumbling past every five to ten minutes all day.

But if you run them far away from where people actually live, then you have the same problem as freight right-of-ways: you’re not actually connecting people to where they want to go, which is usually the entire point of building a transit line.

2. Street-running light rail

Ballpark Cost: $160 million per mile

This is essentially a streetcar with its own travel lanes. Advantages, then, include that it can bypass traffic jams without incurring the expense of building either underground or an elevated structure; it also is much more likely to run near homes and businesses, as it runs in an actual street rather than a freight corridor.

Unfortunately, these kinds of projects can still have problems with speed, since they may have to stop for traffic lights, and being in the middle of a busy street means they can’t reach heavy-rail speeds (the L, for example, can top out at 55 mph – which wouldn’t be allowed if it were running down Western). Still, it’s cheap and user-friendly.

1. Commuter rail conversions

Ballpark Cost: $27 million per mile

It’s a little-known but important fact that there are far more Metra stations on the South Side than there are L stations. Some Metra lines also have freight traffic that limits the number of possible passenger trains, but for the several that don’t – including the Metra Electric District – there’s no reason that these existing passenger rail lines can’t be turned into regular L-type service relatively easily. Make some upgrades, buy some train sets, and run them every ten minutes or so, and boom, you’ve got a new rapid transit line.

Of course, the bigger issue is political. But with Toronto promising 15-minute headways all day on its commuter rail network, it’s a shame there isn’t more momentum for that type of conversion here.

¹ In every case but commuter rail conversions, I’ve come to these cost figures by averaging all similar projects currently under construction in the United States, as listed at The Transport Politic. There are a lot of problems with this: mostly, construction costs are so site- and project-specific that it’s really hard to generalize to a particular development in Chicago from things that are being done elsewhere. But this was, I thought, about as good as I could do – thus the qualification that these are only “ballpark” costs.

In the case of commuter rail conversions, because there is not a single such project under construction in the entire United States (though there is in Toronto!), and because the most likely such project in Chicago – the conversion of the Metra Electric line – has been studied and given a price tag, I just used that.

How we measure segregation depends on why we care

Over at City Observatory, I have a post riffing on recent posts by Nate Silver and the New York Times’ Upshot on segregation and the reproduction of inequality:

That is, it’s easier to send black children to inferior schools if their schools are all on one side of town, and white schools are on the other. It’s easier to target housing and mortgage discrimination against blacks – one of the most important causes of the wealth gap – if all the black-owned houses are in one area. It’s easier to unleash abusive policing and incarceration practices on black communities without disturbing – or even attracting the attention – of whites for decades if whites and blacks don’t live in the same neighborhoods…. If this is why we care about segregation, then Silver’s measure – which doesn’t care which racial groups are mixing, as long as there is some mixing going on – is less useful. What matters then isn’t just integration: what matters is that privileged groups live in the same places as traditionally oppressed groups, so that place-based discrimination is made more difficult. In the United States, that means whites and people of color living in the same neighborhoods. Where that doesn’t happen – even if an area is integrated with, say, blacks and Latinos – then place-based discrimination is still viable, and it will be much easier to reproduce racial inequality.